Can the ordinary resident get justice in Waltham Forest?

Some may judge the question posed in the title of this post as superfluous, with the answer so obviously ‘yes’ that it’s not worthy of further consideration.

But consider these two case studies.

Case One – Mr. A

For some years, Mr. A has lived in a flat at a LBWF sheltered housing block.

In March 2021, he answered a knock on his door, and was confronted by a tradesman who claimed to be from a partner company which LBWF employs to carry out maintenance and repairs.

The tradesman wanted to come into the flat, but was not wearing a face mask and had no ID.

Mr. A was wary on both counts, and so declined to let the tradesman in.

Later, Mr. A went into the block’s common room. Shortly afterwards, the tradesman burst in, still without a mask, and confronted Mr. A at close quarters, shouting and jabbing a finger into his chest.

Mr. A then pulled the emergency cord, and the police attended.

Subsequently, the partner company sent Mr. A a letter of apology and £100 in vouchers.

However, despite the fact that Mr. A wanted the tradesman charged, the police declined, arguing that he ‘had been punished enough’ because – allegedly – he had lost his job and left the borough.

Adding insult to injury, when Mr. A asked to see CCTV footage from cameras in the block, including in the TV room, he was denied access; when he contacted one of his local councillors, he received no reply; and after he complained to LBWF, there was only obfuscation.

Today, Mr. A feels completely let down by both LBWF and the police. He points out that the tradesman (a) put him in considerable danger by not wearing a mask at the height of the pandemic; and (b) without any reason, behaved in a threatening and intimidating manner.

More than anything else, he believes it is the police’s duty to investigate crime, and refer their findings to the Crown Prosecution Service, not substitute for the courts in deciding sentencing.

As of today, Mr. A has not spent the £100 in vouchers.

Case Two – Mr. B

Mr. B lives in a neighbourhood where nine properties within 250 yards of each other have all been tagged with gang-related graffiti twice in a recent 3-month period.

After the first episode, Mr. B reported the matter to LBWF, which, he had established, pledged to remove graffiti from private residences within five working days (or one, if it was offensive).

Happily, the graffiti was removed.

But on the second occasion, the story was very different.

Checking on LBWF’s website, Mr. B found that the earlier pledge had disappeared. Accordingly, he tried to contact the Town Hall to discuss the matter, but after numerous attempts via the online portal, e-mails, and telephone calls, he could not elicit a reply.

In desperation, Mr. B then approached his councillors, who referred him to the ward officer. The Head of Operations for Resident Services got involved, and it was agreed that LBWF would remove the graffiti as a ‘gesture of goodwill’, but made clear that private property owners now had responsibility to make sure their walls were clean, otherwise they would be served with a ‘Defacement Removal Notice’, giving them 28 days to get the job done.

And if the owners didn’t then comply, LBWF would remove the graffiti, but charge for doing so, and place a notice on the property until the bill was paid (invoking a County Court Judgement against the owner).

Mr. B was also advised that he could contact the police, since they kept records of the gangs’ various tags. But this seemingly good news was heavily qualified when Mr. B consulted his local Neighbourhood Watch Co-ordinator, and was advised that the grand total of perpetrators in Waltham Forest who had been caught and fined for graffitiing over the past five years was… zero.

Today, Mr. B feels let down, concluding: ‘This rule change applies throughout the borough, and therefore will impact many other neighbourhoods and private property owners within Waltham Forest.

So I, and many other households, face the prospect of an unknown quantity of cleaning bills of an unknown cost, for beyond the foreseeable future. And it’s all down to the fact that the Police and LBWF don’t exercise their powers to stop and fine offenders’.

What explains Mr. A and Mr B.’s travails – their struggle to attract the attention of the authorities, and their ultimate failure to attain apposite restitution?

Were they both just exceptionally unlucky? Or is there a less comforting explanation?

To begin with, it is important to stress just how distressing crime and anti-social behaviour (ASB) continue to be for many of those living in Waltham Forest.

Recent LBWF research finds that ‘Half of residents say they are worried about anti-social behaviour’, and ‘almost two-thirds…say they are worried about crime’. Little wonder that ‘Crime and fear of crime’ is said to have ‘a strong effect’ on one-third of residents’ lives.

However, when it comes to reporting crime and ASB, or being involved in discussions about how to address the issues, the options for most people are rather bleak.

Over the years, the police have closed all but one police station, and urged that communication with them should be made by phone or via social media. But the reality is that, outside of 999 calls, this is easier said than done. For example, a recent LBWF report refers to ‘the common complaint from residents about lack of Police response on [non-urgent telephone number] 101’.

The situation at the Town Hall is rather similar, with residents regularly reporting that it is difficult to contact officers directly, and, on occasion, little indication anyway of who is responsible for what.

It’s true that residents can take their concerns to a network of Safer Neighbourhood Team (SNT) ward panels, plus the borough-wide Safer Neighbourhood Board (SNB), but again these are not necessarily satisfactory options.

Some of the SNT meetings are well advertised and run, others much less so, while as to the SNB, though in theory it is supposed to give residents and victims ‘a greater voice around crime prevention and reduction’, in practice it appears to be in near constant crisis, with a recent report concluding it is riven by ‘open hostility and antagonism’, ‘not representative’, and ‘introverted’, ‘addressing internal issues and conflict rather than focusing on holding the police to account and engaging with the wider community’.

Significantly, in the past year or so, both LBWF and the police have tried to address this communication deficit by implementing new strategies aimed squarely at particular localities, for example, ‘Operation 20x20x20’, 20 commitments from police to provide 20 solutions to residents’ key concerns in 20 wards.

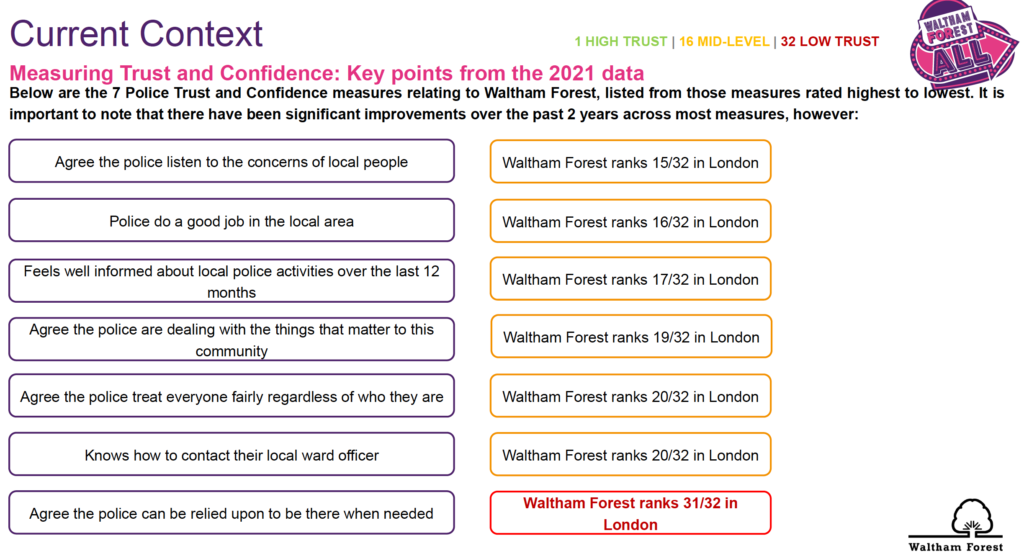

But whether these have worked is debatable. Even some councillors on the LBWF Communities Scrutiny Committee are hazy about ‘Operation 20x20x20’. Moreover, though police polling which measures ‘trust and confidence’ in the force throughout London reveals that, on most metrics, Waltham Forest is mid-range, when asked ‘do you agree the police can be relied upon to be there when needed?’, locals answer less positively than anywhere else in the capital:

Beyond the communication and involvement issue, there seem to be differences between what the public and the authorities believe are the core strategic priorities. One way of illuminating this is by examining a very striking example – the comparison between burglary and hate crime.

First, some basic numbers.

In the two years January 2020 to January 2022, official police figures show that there were 3,279 residential, business, or community burglaries in Waltham Forest, and 92 per cent went unsolved (that is, there was no resulting sanction, such as a charge or caution).

It’s difficult to produce a single comparative figure for hate crimes, as the categories used overlap. But some idea of the magnitudes involved can be gained from the fact that, over the same two-year period, there were 161 such offenses concerning ‘homophobia’, 64 concerning ‘Islamaphobia’, and 26 each concerning ‘anti-semitism’ and ‘disability’; and, when all four are taken together, 90 per cent went unsolved.

Turning to public perceptions, LBWF research regarding the offenses that residents are ‘most worried about’, identifies the top three as burglary, knife crime, and drug dealing, with hate crime unmentioned.

Given this kind of evidence, it is reasonable to assume that LBWF and the police to some extent must be prioritising burglary over hate crime, but surprisingly, the reality is exactly the opposite.

A search through the relevant public sources identifies no special measures or extra resources to target burglary, and no sustained debate about how it might be mitigated.

Indeed, the impression given is that burglary must be accepted as a fact of life, unpleasant, of course, but not really addressable, let alone eradicable.

By contrast initiatives to tackle hate crime are numerous and high profile. In 2020, LBWF convened a citizens’ assembly to recommend hate crime strategies, and has subsequently devoted considerable resources to related campaigning and training. The police employ a dedicated hate crime officer; offer ‘an anonymous email inbox…for those experiencing hate crime in the borough’; and have ‘increased patrols, identified hot spots, and engaged with local communities groups [sic], faith groups and the LGBT+ community’. As a senior officer recently explained to the Communities Scrutiny Committee, they are even ‘revisiting all previous reports to see if hate crime had been a factor’, as well as ‘monitoring social media to keep an eye on any trends’.

The point which emerges is that policies on crime, and how to reduce it, are sometimes influenced less by evidence, more by political fashion, and/or campaigners with pre-determined agendas.

That Mr. A and Mr. B were treated in the way described was likely not because of bad luck, therefore, but because their cases fell outside the boundaries of what the authorities deemed worthy of substantive response.

The concerning fact is that there must be thousands of other residents who either already have found themselves similarly marginalised, or will meet the same fate in the future.