LBWF fraud team’s investigation of the FEDs fire safety scandal dodges key questions, as officers focus on their ding dong battle with Osborne at the High Court

In response to a Freedom of Information request, LBWF has just released a redacted version of the June 2021 investigation report, authored by the internal Corporate Anti-Fraud Team (CAFT), concerning the flat entrance door (FED) scandal, much discussed previously on this blog.

The ‘executive summary’ of the findings reads as follows:

‘Osborne Property Services Ltd (OPSL) were contracted by LBWF to provide 219 fire doors to the following blocks: Holmcroft House, Lime Court, Boothby Court, Northwood Tower and Goddarts House.

Originally LBWF requested…that these doors were FD30 rated (provided 30 minutes of fire protection). This is in line with Building Regulations 2010.

This order was then changed (between 6th November 2017 to 13th February 2018) to request FD60 rated doors instead (providing 60 minutes of fire protection)…

The doors that are FD60 rated cost £XXX [redacted] more than the FD30s and LBWF were charged accordingly.

OPSL employed the services of their subcontractor, Exterior Plas Ltd (EP), to provide and install the fire doors. EP ordered the doors from the manufacturer Masterdor Ltd.

Specification Certificates were provided by EP to OPSL stating that the doors were of a FD60 standard.

In 2018 Building owners were required by the MHCLG [Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government] to check the compliance of Front Entrance (Fire) Doors… Fire testing conducted in accordance with BS476- 20/22:1987 on 12/6/2019 and 6/11/2019 by Thomas Bell-Wright International Consultants has since shown that the doors that were installed fall below the FD60 standard. Results show that the 3 doors tested provide 34, 31 and 45 minutes of fire protection. It is important to note that they do however still comply with building regulations as stated in Building Regulations 2010, Fire safety, Approved document B.

There is no evidence to suggest that OPSL (or indeed EP) were aware that the doors were not of the standard requested by LBWF (FD60)…

Therefore, there is not a case to pursue against OPSL in regard to the Fraud Act, 1968, as this requires the perpetrator to make a dishonest representation’.

So, there’s been no fraud, and as LBWF is fond of saying to its interrogators, ‘It’s time to move on’.

But can the CAFT report be considered the last word on the matter? Does it stand up to scrutiny?

The first point to make is that, in reaching its judgements, the CAFT relied upon only a small amount of evidence, essentially written sources that were already in the public domain – the LBWF order forms, some of the Masterdor specification certificates, and the Thomas Bell-Wright International Consultants test reports.

Conversely, it conspicuously failed to examine a wide range of other relevant documentation, most obviously e-mails, and nor did it interview witnesses, for example council officers and employees of Exterior Plas and Osborne.

Moreover, the CAFT also seemingly had several blind spots.

Thus, the fact that LBWF changed its initial order, requesting FEDs that were FD60 rather than FD30, is noted, but not examined, curious because the former were by some margin more expensive, while the latter had been widely used elsewhere, and allegedly satisfied the Building Regulations minimum (a standard that, in this and most other contexts, LBWF emphasised was entirely adequate).

Similarly, the discussion of why some FEDs were tested foregrounds government post-Grenfell advice and warnings, but ignores other relevant factors, most importantly one senior officer’s frank July 2019 admission to a ministry official that the tests were undertaken because LBWF wanted to ‘progress a claim’ against Osborne (of which more later).

Finally, there is the issue of certification.

It is an industry-wide convention that manufacturers provide purchasers with a certificate for each FED they buy, listing its unique factory reference number and the quality tests that it has satisfied, in order to preclude any mix-ups that might jeopardise fire safety.

In its investigation report, the CAFT makes three statements about certification:

‘2.6. Specification Certificates were provided by EP to OPSL stating that the doors were of a FD60 standard…

5.13. Certificates from Masterdor Ltd were received by EP for the doors installed in Boothby Court…Holmcroft House…and Lime Court… Each certificate states that the door was manufactured in accordance with Fire Test Report (FD60s) BMT/FEP/F15137C…

6.2. Certificates provided by the manufacturer of the doors Masterdor Ltd to EP suggested that the doors were of a FD60 standard’.

None of these statements are wholly untrue, but neither can they be said to give an accurate impression of the whole story.

For though, courtesy of ET, LBWF now has possession of the 100 certificates for the FEDs at Boothby Court, Holmcroft House, and Lime Court, the whereabouts of the 117 certificates for the FEDs at Goddarts House and Northwood Tower remains unknown, and this despite the fact that they were directly requested from Masterdor Ltd. before it went into administration in March 2019, and, more recently, Osborne.

Once again, therefore, CAFT’s stance seems surprisingly incurious. After all, the evidence is that (a) someone at LBWF without explanation changed the FED order to costlier FD60s; (b) over half of the certificates for the FEDs in this order are still missing; and (c) as was public knowledge at the time, from 2016 onwards Masterdor Ltd. was wrestling with serious financial difficulties.

Surely, even in Waltham Forest, that’s enough to merit a paragraph or two?

In conclusion, the CAFT report is shallow and unconvincing, and reads as if commissioned to swiftly dispose of an inconvenient chore, rather than pursue the truth.

How can this patently flawed approach be explained?

It is worth noting to begin with that, because of redundancies and associated policy changes, the CAFT today is a mere shadow of what it was even a handful of years ago, and has only limited capability for sustained investigation.

But that accepted, what’s probably shaped outcomes most is the fact that, as already noted, LBWF has been, and remains, involved in litigation with Osborne.

The details can be summarised as follows.

In the spring of 2019, LBWF ended its relationship with Osborne, and entered into a replacement contract with Morgan Sindall Properties Services Ltd..

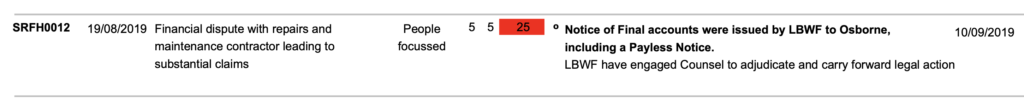

Then, in September of the same year, the Audit and Governance Committee was informed that LBWF’s strategic risk register included a new entry, its unusually high numerical rating highlighted in red:

Subsequently, the same committee has received updates to the register on a regular basis, but with the bulk of material about the Osborne dispute withheld from the published record under stipulations of the Local Government Act 1972 (which in certain circumstances can make ‘Information relating to the financial or business affairs of any particular person (including the authority holding that information)’ confidential).

However, from looking at other sources, it transpires that, first, the FEDs issue has become subsumed into the wider litigation, on the basis that, the fraud issue aside, Osborne is alleged to have breached its contractual obligations to supply goods as specified when ordered; and, second, that though LBWF initially banked on a swift vindication, no such thing has happened, primarily because Osborne is counter-claiming, meaning that as of today, the two parties – as far as anyone knows – are still slugging it out at the High Court.

In this situation, it is easy to see why the CAFT investigation was so superficial: the litigation with Osborne is the main event.

Of course, as part of the court case, LBWF may be interrogated about some of the issues raised here.

But LBWF no doubt takes comfort from the fact that its answers will be heard far from the local public’s gaze, with (if past experience is anything to go by) even the outcome of the litigation remaining unknown.

PS for an earlier fraud report which resulted in litigation, see the link below featuring EduAction.