The Labour Left in Waltham Forest: neither use nor ornament (2)

A previous post looked at the antics of the Waltham Forest Labour Left (see link below) and predictably prompted an abusive tirade from the Corbynistas and Toytown Trots who control parts of the local Party.

Much of this was personal in nature, amusing evidence that, for all their avowals about embracing a kinder and gentler politics, when criticised, they soon regress to the playground.

However, amongst the childish verbiage, was a more substantial allegation – that in documenting LBWF’s many faults, this blog consistently has overlooked the damaging impact of Tory cuts from 2010 onwards, and thus inexcusably failed to name and shame those who are the real villains of the piece.

This claim, of course, is very common on the Labour Left, indeed has become almost an article of faith, trotted out at the drop of a hat, and accordingly it’s worth examining in more detail.

In short, has LBWF been martyred on the altar of a political-inspired austerity?

To begin with, some historical perspective is salutary.

For only minimal digging shows that long before the Tory cuts hit, in the early Twenty-First Century years of Blairite milk and honey, LBWF was already well in the mire.

A few examples are illustrative. In 2003, the Audit Commission’s Comprehensive Performance Assessment (CPA) ranked LBWF in the bottom 10 of 150 English local authorities, and worse than all but one in London. Subsequently, LBWF became entangled in a number of scandals concerning wasted money, with those involving Dr Foster and the Neighbourhood Renewal Fund (NRF) receiving considerable public attention (see links).

In 2009, LBWF finally appointed an Independent Panel to investigate, and the latter issued what the BBC described as a ‘scathing’ report, which found evidence of, amongst other things, ‘a deep-rooted culture of non-compliance with procedures to prevent fraud’, and described the Town Hall as ‘insular and secretive’ (see link, and document in side panel, left).

In the light of these facts, the Labour Left’s narrative begins to look decidedly shaky. But to settle the matter once and for all, it is obviously necessary to take the bull by the horns, and examine the years of austerity themselves, in order to assess directly how LBWF fared, and that means turning to some of the local authority’s own data sets.

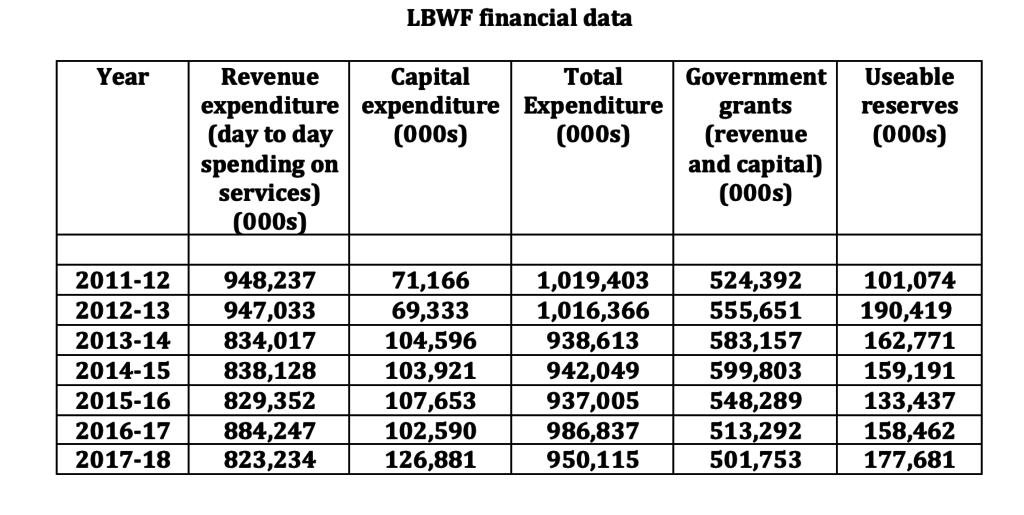

First, some caveats. Accurate staff headcount figures are difficult to come by for some years. Following revenue and expenditure categories across time can be hazardous because of reclassifications. The monetary sums that follow are not adjusted for inflation. And because of the way that LBWF has published its accounts, meaningful comparison is anyway only possible for the years 2011-12 to 2017-18, rather than the more appropriate 2009-10 to 2019-20.

But that said, the exercise is not without its interests.

One impact of the period immediately stands out: in the six years after 2011-12, the council workforce declined significantly, from c. 6,500 to c. 4,000, and much of this was the result of redundancies, with all the personal dislocation and heartache they inevitably entail.

Nevertheless, if such human considerations are set aside, and LBWF is assessed solely in terms of its hard financial performance, a more nuanced picture emerges.

Revenue expenditure (day to day spending on services) fell from its 2011-12 peak to its 2017-18 trough by 13 per cent, but over the same period capital expenditure rose 78 per cent, meaning that expenditure as a whole was only 7 per cent down.

Perhaps unexpectedly, too, Government grants increased every year to 2014-15, before then falling away; while LBWF appears to have opted to run a fairly aggressive reserves policy throughout, with the sum put aside in 2017-18 some 76 per cent bigger than that for 2011-12.

Of course, these trends need to be contextualised in terms of wider changes that were simultaneously transforming the borough.

In the decade following the 2011 census, the population of Waltham Forest is estimated to have grown by 10 per cent, meaning a big jump in demand for statutory council services.

On the other hand, many of the incomers were young, affluent professionals, who helped push up average local house prices by 95 per cent in 2015-20 alone, and this in turn increased the annual council tax take; while the general air of prosperity meant that LBWF was for the first time courted by national and international property developers, leading its chief executive, Martin Esom, to boast ‘This is our moment in terms of values going up and the interest being there…We’ve estimated the total value of development opportunity as £1 billion’.

A final point worth highlighting is that, whatever austerity’s precise impact, it was certainly never all-embracing, and from some angles, the Town Hall seemed to remain surprisingly buoyant. The average annual take home allowance for councillors stood at £13,883 in 2010-11 but £18,109 in 2017-18, an increase of a third; the number of officers earning £50,000 or more grew from 127 to 146 between the same dates; and despite his centrality to Town Hall operations, Mr. Esom was permitted to take on two extra outside jobs.

Moreover, LBWF continued to invest millions, plus substantial amounts of staff time, in vanity projects, from relatively minor matters like placing flag poles in front of council properties; through gifting deadbeats like the E11 BID Co. and North London Ltd. hundreds of thousands of pounds without much concern for how it was being spent; all the way up to really big-ticket items like the Borough of Culture jamboree and Walthamstow Wetlands.

Plainly, austerity caused pain for council staff who were axed, together with some degree of reduction in service levels, but to suggest that LBWF was screwed to the floor at this time, hamstrung from making choices at every turn, is well wide of the mark.

A final reason for doubting the Labour Left’s preoccupation with austerity is that it doesn’t help much in understanding the numerous case studies which have been presented on this blog. For what the latter show, again and again, is that, when malfeasance has occurred, it can be traced, not to a lack of money, but to a failure to follow simple and well-known procedures, which, in turn, suggests that the deeper problem throughout has been LBWF’s internal corporate culture.

It was the Independent Panel which first made this connection, believing that LBWF’s determination to rise up the CPA league table had encouraged ‘almost a recklessness to get work done rather than doing it through the proper processes’, and simultaneously led to the general downgrading of ‘compliance’.

The outcome was a situation where large sums of money were being spent without even elementary controls, as this example illustrated:

‘Under its NRF-funded Youth at Risk programme, Waltham Forest entered into a contract worth £240,000 with EduAction. There have been numerous complaints through whistle blowers and a number of Freedom of Information (FOI) requests around this contract. It has been impossible to find any individual within the Council itself who understands what was contracted and what has been delivered for the money. Of even more concern, there appears to be little concern from key people that this is the case’.

What made the situation worse, in the Independent Panel’s view, was that the Town Hall had become increasingly secretive, and in addition lax in enforcing standards amongst its workforce. One paragraph jumped off the page:

‘There have been references to a number of disciplinary investigations. However, there is no evidence that there is any follow through on these. The timescale for closure is protracted and individuals have either left the Council or there is no case to answer. This is disturbing in that improper action with no consequence is not a deterrent. Non compliance with rules can easily become acceptable behaviour and even be condoned just to get the job done’.

In the years that followed, LBWF repeatedly promised to put its house in order, but whether previous infelicities are now banished for good is by no means clear.

Much of the difficulty in reaching a conclusion about this stems from the fact that, simultaneously, LBWF has made increasing efforts to ‘control the narrative’, beefing up its PR capability, and actively trying to prevent some kinds of information surfacing in public. Indicatively, by 2020, its treatment of residents who asked questions under the Freedom of Information Act had become so offhand, even deliberately obstructive, that the Information Commissioner’s Office was moved to issue a strong public rebuke, something it had not done in relation to a local authority since 2009.

Such attempts at constricting transparency notwithstanding, however, there are noteworthy straws in the wind.

Recent scandals – for example, those involving the East London Credit Union, and then fire safety – are replete with familiar blunders. More pertinently still, a late 2019 LBWF Internal Audit and Anti-Fraud Team report on Town Hall procurement lambasted significant ‘non-compliance with existing Rules’ – exactly as the Independent Panel had done a decade before.

None of this reflects well on the Waltham Forest Labour Left. Its parrot cry that everything which has gone wrong in the Town Hall can be blamed on Tory cuts is revealed to be a misleading oversimplification. Conversely, it has nothing to say about where the real issues are to be found.

Postscript

Since John Cryer’s forthright statement of late 2020 (see link), the Waltham Forest Labour Left has gone into ‘save Jeremy’ overdrive, simultaneously berating those who it accuses – in that tired cliché – of ‘weaponising anti-semitism’.

However, the blunt truth is that, as the Starmerites increasingly assert their authority, the Left here, as elsewhere, and Corbyn or not, seems headed for a dead-end, chuntering away to itself in an echo chamber of tweets and memes, but otherwise lacking any power or relevance.