LBWF and settlement agreements: a bellwether in the post COVID-19 years

In the post COVID-19 years, it will be imperative that LBWF spends money wisely, and turns its back on past profligacy.

The fact that LBWF’s Chief Executive currently earns substantially more than the Prime Minister is palpably absurd, and urgently needs rectifying, but there are also several other possible ways of making enduring savings.

In February this year, the Taxpayers’ Alliance (TA) investigated local authority use of settlement agreements, with the latter defined as follows:

‘Settlement agreements are legally binding agreements between an employer and an employee that set out the terms surrounding the termination of employment. The purpose of settlement agreements is to resolve any disputes between the two parties that could not be resolved as part of internal procedures, and prevent future related claims. Settlement agreements often (but not always) result in the employer paying the employee, whether that be, for example, through compensation for loss of employment or payment in lieu of notice’.

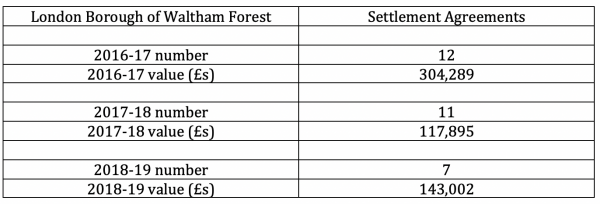

As regards LBWF, the TA found that it had used settlement agreements 30 times in the last three years, paying out a total of £565,186, broken down thus:

So much for the facts. Are they anything to get concerned about? Isn’t a settlement agreement just a routine component of hiring and firing?

It is important to underline that settlement agreements often include non-disclosure clauses, and it is where this happens that disquiet is at its most acute.

One allegation is that local authorities resort to such tactics in order to prevent whistleblowing. Four years ago, to quote an example, the Guardian reported:

‘Several teachers forced out of schools at the centre of the Birmingham Trojan horse scandal were offered settlement agreements. The teachers raised concerns about governing bodies that were trying to introduce strict Islamic principles…A government report on the scandal found there was a perception among staff that the city council preferred to move teachers on rather than confront misbehaving governing bodies’.

In other cases, the driver is said to be a fear of broader reputational damage. Any employee who feels mistreated has the right to take their case to an employment tribunal. How much better for a local authority to engineer a pre-hearing settlement on confidential terms, and thus prevent possibly embarrassing evidence from being reported in the press.

Finally, and more speculatively, it has also been suggested that settlement agreements are on occasion engineered as a discrete way to reward favoured senior officers when they decide to move on – a way, in other words, of buying enduring loyalty, and making sure that the inner circle’s secrets remain forever buried.

None of these uses are creditable.

By getting rid of settlement agreements altogether, therefore, LBWF will not only save money, but simultaneously boost its organisational integrity.

In short, this is, perhaps more than most, a bellwether issue, one that will indicate whether LBWF is constructively adapting to the new conditions, or stubbornly clinging to the infelicities of the last two decades.