The Connecting Communities Programme in Waltham Forest: everyone’s welcome (except the disabled and poverty-stricken)

In March 2018, the government launched a new £50m. Integrated Communities Strategy (ICS), ‘to tackle the root causes of poor integration and create a stronger, more united Britain’.

Shortly afterwards, it was announced that LBWF was to be one of five authorities in England involved in piloting the ICS to 2019/20, supported by an initial grant of £1.2m.; and subsequently, LBWF has published Waltham Forest Our Place. A Shared Plan for Connecting Communities [hereafter Our Place], an implementation document aimed at the general public.

What follows outlines LBWF’s intentions, and then offers a critical evaluation.

Our Place opens with some background. Waltham Forest’s population increased by 17 per cent between 2007 and 2017, and is expected to rise by a further 6 per cent over the next five years. The borough is very diverse: ‘Around two thirds (64%) of children and young people in Waltham Forest are from BAME (Black, Asian and minority ethnic) groups compared to 50% in [the] overall population’.

The deprivation of the past has diminished, and affluence is spreading. Nevertheless, there are ‘significant social challenges’. About one in five of all residents have ‘difficulty speaking English’. Child and ‘in work’ poverty persist. While the number who are economically inactive ‘is at its all-time lowest…44% of working age women of ethnic minority background are economically inactive compared to 18% of white females’.

In addition, social connections are said to be ‘very narrow’, with, for example, a majority of residents maintaining friendships primarily with those from similar backgrounds, whether in terms of ethnicity, educational achievement, or income level.

Our Place’s fundamental purpose, therefore, is to outline a targeted response: ‘If social isolation or exclusion is the problem, whether due to poverty, discrimination, lack of confidence, language barriers, mobility issues – then social integration – through strong community connections – is the tonic’. The balance of the document explains how.

First off, Our Place promises a way of working that is both ambitious and innovative. Contrasting with earlier programmes which are characterised as ‘top down’, the approach taken is to be ‘much more collaborative…relying not on interventions but on social connections and relationships as a catalyst of change’. LBWF will have ‘a critical role to play in providing clear and positive leadership and resources’, true, but ‘ultimately the community needs to own…[the] agenda’. The aim is to create ‘a movement not a project’, one that ‘people buy into because it chimes with their values’, and as a consequence will be happy to then ‘run and make their own’.

As regards the detail, Our Place proposes three interlinked innovations – ‘a new…communications campaign which calls on everyone in our borough to act, engage and participate’; ‘new Community Networks for Leyton, Leytonstone, Chingford and Walthamstow’; and ‘new opportunities to enable people to connect with and help each other’ – plus a host of specific policies, grouped under the following seven headings:

‘A new ESOL [English for Speakers of Other Languages] offer’

‘Supporting people into work’

‘A new offer for new arrivals to the borough’

‘A stronger approach to social integration and opportunity for young people’

‘A new programme to address gender inequality’

‘Family to family support’

‘Enable greater opportunities for older people to be part of the place they live [sic]’

The hope is that, by pursuing this agenda, ‘at least 50,000 people’ will be energised ‘to do positive things for their community’, and so cohesion will be measurably enhanced.

Self-evidently, Our Place is in part uncontroversial. If some of those coming to the borough find English a challenge, it makes sense to help them become more fluent. Similarly, there is surely nothing wrong with addressing the social isolation that can accompany old age – indeed (with only limited council support) Age UK Waltham Forest has been prioritising this for many years.

Nevertheless, that said, there are other significant aspects of Our Place which are certainly questionable.

The first concerns governance. As has been noted, LBWF makes much of its determination to put the community in the driving seat, create of a popular movement, etc., yet Our Place is notably silent about the nuts and bolts of real-time administration.

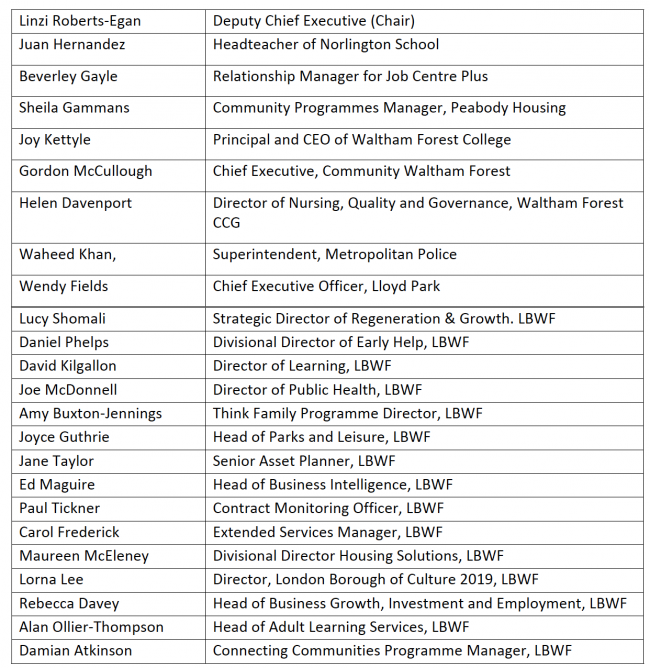

However, a little investigation reveals that a Cabinet paper of December 2018 – Connecting Communities Strategy – prefigures Our Place, and is rather more forthcoming. Responsibility for day to day implementation will rest with ‘a small team’ of LBWF officers, overseen by the Waltham Forest Connecting Communities Partnership Board, described as bringing together ‘the local authority and a range of public and voluntary sector partners’, and comprising the following:

This is surprising, to say the least. As regards the composition of the Board, 15 of the 23 members are senior LBWF officers; there is no practitioner from the local community and voluntary sector (presumably reflecting the fact that for many years now the latter has viewed the council with disdain); while ordinary residents, supposed to be at the heart of the programme, are also conspicuous by their absence.

If this isn’t ‘top down’, then what is?

That’s bad enough, but there is worse. LBWF touts Our Place as ground-breaking. Yet the governance system being used in fact largely follows past practice. And what’s alarming is that, when used previously, the results left much to be desired.

At first sight, it seems sensible to pack such bodies as the Connecting Communities Partnership Board with senior figures, so as to draw on their authority and expertise. Yet experience shows that, with a host of more pressing priorities connected to their primary responsibilities, many of this cohort understandably will tend to go AWOL. Meanwhile, delegating all the detailed work that a programme of this type entails to a restricted number of junior colleagues is fraught with risk, because in a pressured environment, the probability is that back office tasks like tendering and monitoring, crucial to ensuring that public money is being spent proficiently, will fall by the wayside.

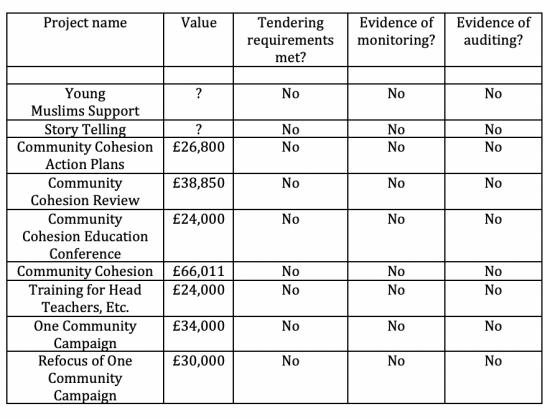

One by no means atypical historical episode (the full story is linked to below) serves as a warning. In 2006-07, LBWF embarked on a similar tranche of community cohesion projects, run using almost exactly the same set up. Later, PricewaterhouseCoopers was brought in to conduct a review. What it uncovered was shocking:

How will such mistakes be avoided this time round, when all public sector organisations are so much more stretched?

Equally concerning is the way that LBWF plans to involve local residents. As already noted, Our Place pledges ‘collaboration’ and ‘co-production’, while also suggesting that peer to peer interactions will play a big part in achieving outcomes. This all sounds alluring, and of course suitably flatters likely grassroots participants. But a moment’s thought reveals some obvious difficulties.

First, if residents, as promised, are to be effectively empowered in decision-making at local level, for instance over the design and financing of individual projects, they will need information – about possible alternatives, about the track record of potential specialist contractors, about progress with agreed goals, and so on – and moreover need it in apt fashion, tailored to the cycle of key meetings, primarily those of the four new Community Networks. But given that officer time almost certainly will be at a premium, is it likely that this essential condition will be met? And if it is not, won’t the agenda in reality be dominated by an unholy trinity of those with loud voices and sharp elbows, the LBWF hierarchy, and outside professionals?

Likewise, while peer-to peer mentoring sounds appealing, a lot depends on how it is managed. If mentors are given appropriate training and supervision, fine. But if the prejudiced or ill-informed are simply let loose on the vulnerable, well, the dangers are obvious.

A final set of difficulties stem from LBWF’s avowed focus – its understanding of, first, who is marginalised or excluded, and thus in need of assistance; and, second, the range of barriers that hinder greater inclusion.

Our Place takes what it describes as ‘[a] broad approach to “social integration”’, promising ‘an agenda that embraces everyone in our community’. However, it simultaneously refers to ‘key priority groups’, and clearly slants actions towards some residents rather than others.

Once again, Connecting Communities Strategy is a good deal more forthcoming, bluntly declaring: ‘In line with our strategic priorities, our innovations will be focused on a number of key cohorts: Young people and families, Older people, BAME women, [and] New arrivals’.

One obvious question is exactly why these four ‘key priority groups’ have been chosen, and it has to be said that the answer is not always clear. Neither Our Place nor Connecting Communities Strategy say anything much about older people in Waltham Forest, simply asserting that they may be socially isolated.

BAME women make the cut, as already observed, apparently principally because they are likely to be less economically active that their white peers.

However, whether the white/BAME comparison is necessarily useful appears debatable. For national series, at least, indicate a rather more complicated picture. The broad contrast between white women and BAME women stands, with 73 per cent of the former, and 56 per cent of the latter in employment.

But what’s striking is that within the BAME category the differences are much bigger, so that for example, while 66 per cent of Indian women and 64 per cent of Black African/Caribbean women are in employment, the comparative figures for Pakistanis and Bangladeshis are 39 per cent and 30 per cent respectively. If the objective is really to prioritise, would not it be better to concentrate on the latter, rather than pretend that everyone included under the BAME umbrella is equally disadvantaged? Here, as elsewhere with Our Place, it seems that narrow political considerations – the desire to play to the gallery – may have distorted the analysis.

So much for those considered a priority, but it is very striking, too, that some obvious potential candidates have been overlooked.

Disabled people have good reason to believe that in general they are likely to be more excluded than anyone else, but for some reason in this context they go all but unmentioned.

Virtually the same goes for the poor. Our Place, it is true, does reference ‘The family struggling to raise their children in a context of poverty and poor housing’, together with the fact that ‘a third (36%) of children in our borough were estimated to be living in poverty after housing costs are accounted for’. But the incontrovertible fact that lack of money is a major barrier to social inclusion – indeed, perhaps the major barrier – is not discussed in any great detail, and nor are there any directly related ameliorative policies.

Finally, as regards defining the factors which militate against cohesion, LBWF is again puzzlingly partial, in particular ignoring evidence that both political and faith institutions in Waltham Forest are a central part of the problem, disconnected from residents and responsible for generating mistrust.

Recognition of this debilitating situation has echoed down the years. Thus, a 2007 report by the respected Institute of Community Cohesion noted of the borough’s ‘Muslim communities’:

‘As in other boroughs, communal politics prevail, and Councillors from one particular community or group are perceived as working only in the interests of that group, rather than all the people living in the ward they represent.

Similarly, Council officials from the Muslim communities are perceived by many to be partisan, and we understand that some have been placed under inappropriate pressure by Councillors or other members of their own communities’.

Seven years later, the Open Society Foundations convened focus groups in two local wards, and made similar observations:

‘White working-class people revealed a jaundiced view of politics at the local and national level in the focus group discussions. The general opinion was they had neither voice nor influence.

Similarly, British Muslim communities were critical of local leaders who purported to represent their interests. Consistent complaints included the poor quality of political representation on the local authority. It was suggested that some Muslim councillors did not have the capacity to advocate and some could not speak English. There was also much scepticism about the role of faith institutions like mosques, which are characterised by a parochial approach to faith and politics, little participation and periodic infighting’.

It might be expected that any fresh initiative on cohesion would routinely re-examine such matters, but clearly in the Town Hall at least, sensitivities dictate they are now considered taboo.

Turning to the implementation of Our Place, LBWF currently is in the process of appointing programme staff, and has initiated one or two of the promised events, notably a Community Network meeting in Leytonstone which (amusingly) was almost exclusively middle-aged, and an open Iftar breakfast at the Town Hall, allegedly attended by 700 participants, including (in the view of the presiding councillor) ‘young children, teenagers, different ethnicities, [and] people of all faiths and none’.

As to the future, LBWF pledges that since it is ‘committed to rigorous evaluation’, the Connecting Communities Board will review ‘key milestones [at] three, six and nine months’, and publish an annual report this coming autumn ‘setting out the progress we have made in 12 months and the learning from our work so far’.

So watch this space (though don’t hold your breath!).