Silver Birch Academy Trust: Lost in the Forest?

As this blog has periodically observed, to mere mortals the world of primary and secondary school academies, and in particular their governance, is sometimes rather puzzling.

Last Sunday, the Observer featured a local case that well illustrates the point.

Silver Birch Academy Trust (SBAT) runs four primary schools with nearly 2,000 pupils, three of which (Chingford Hall Primary Academy, Longshaw Primary Academy, and Whittingham Primary Academy) are in Waltham Forest.

Like its peers, SBAT is regulated by the Education and Skills Funding Agency (ESFA), and subject to periodic inspection.

Where the controversy arises is that, according to the Observer, when ESFA inspectors recently visited SBAT, what they found was rather concerning, with their draft report, amongst other things, apparently alleging that:

(a) recent spending included almost £10,000 on Facebook adverts for a free school that has not yet been set up; £6,117 on a fact-finding trip to China and New Zealand for the chief executive and her deputy; £99,000 (£10,000 without quotes) refurbishing a former caretaker’s house, subsequently to be rented out to a member of staff, though as yet no money seems to have changed hands; £3.26m on services from six companies without there being evidence of contracts having been signed; and nearly £5,000 on four laptops for management;

(b) one of the constituent schools spent £1,064 on two rooms for two nights at the Hyatt Regency hotel, Birmingham, with £507 of this for a room where the guest did not turn up;

(c) contracts existed with four consultancy companies, together worth £326,044, without the work having gone out to tender; and

(d) those in senior positions seemed hazy about finances, unable to explain ‘”the in-year deficit that the trust incurred”’ and indeed uncertain about ‘“what an in-year deficit was”’.

It is absolutely right to underline, first, that the document seen by the Observer is just what the paper describes it as, a draft, and the finished version may or may not repeat these allegations; plus, second, when contacted by the Observer, SBAT responded by stating amongst other things that some of the payments made ‘”were…in accordance with trust policies and procedures”’, while ‘“Changes already under way and further measures introduced in response to the ESFA enquiries have dealt with many of the points raised”’.

However, it is also reasonable to add that there is some interesting history here. For a bit of digging around reveals that in 2014, following disclosures by whistle-blowers, the Department for Education’s Internal Audit Investigation Team also looked closely at SBAT, and it too came to some fairly striking findings (the redactions are in the original):

‘Management Summary

4. The investigation has not identified fraudulent action by the Trust but has identified concerns in relation to poor procurement practice where it has not been possible to establish that a proper process has been followed by the Trust when undertaking a number of procurements.

5. The 2013-14 contract (SLA) for providing ICT services to Whittingham Primary Academy was awarded to <redacted>.The Chair of Governors for the academy works for <redacted> which is a mutual organisation that provides ICT support to numerous schools in the area. The company will also be providing ICT support to the other academy in the Trust. There was inadequate supporting documentation for the decision to award the contract (SLA) to <redacted> at a cost of £22,172 (ex VAT) per academy per year against lower quotes from two other companies of £20,096 (ex VAT) and £5,219 (ex VAT). The justification for allocating the contract to the company was demonstrated at a later date following further work by the Business Manager (BM).

6. The Executive Headteacher (EHT) and the BM explained that the rationale for going with <redacted> was that the contract provided a high level of support, including on-site support, an IT coordination role including training for staff and network and service support rather than just a call centre based support operation. The Chair of Governors had declared a business interest in the minutes of Governing Body meetings.

7. Offices at both academies have been refurbished. The office refurbishment at Whittingham Primary Academy has been completed at a total cost of £56k. The Whittingham Primary Academy ‘Financial Management Policy and Code of Practice’ states that goods/services with a value over £25k, or for a series of contracts which in total exceed £25k must be subject to formal tendering procedures. The office refurbishment work was carried out by a company entitled <redacted>, the work was not put out to tender by the academy. The reason given was that only this supplier could provide the particular furniture required and that they already supplied a number of local academies.

8. The purchases included a number of items for the EHT office/meeting room, a conference table (£4,887 ex VAT), 14 executive conference armchairs (£4,998 ex VAT), a fridge unit (£1,687 ex VAT) and four plant pots of which 2 are located in the EHT’s office/meeting room (£780 ex VAT). In total the cost of the furniture refurbishment for the EHT’s office/meeting room was £25,996k (ex-VAT). We have not seen a business case to support the assertion that these represented value for money.

9. The Whittingham Primary Academy ‘Financial Management Policy and Code of Practice’ states that at least three written quotations should be obtained for all orders between £5k and £25k. We found 14 separate invoices from the company for 6 different dates in relation to the £56k total, none of the invoices had a value that was greater than £5k (ex-VAT). For one of the dates there were 7 invoices totalling £24,315 (ex-VAT), none of these invoices were for a value in excess of £5k and for 4 of the invoices the value was just under £5k (ex-VAT). Similarly, two other invoices were found for the same date, the value of each was again just under £5k (ex-VAT).

10. The EHT stated that there was no intention to split payments and this was not an attempt to avoid the need for written quotations. She stated that the furniture is good quality that will not need to be replaced in future and will mean that the academy can generate income by renting the office/meeting room out for external meetings to provide income to the academy.

11. The Trust have commissioned work in the region of £200k for refurbishment of the main Whittingham Primary Academy building. The robustness of the tender process has not been demonstrated by SBAT and we have been unable to confirm from the available documentation that a full and open tender, in line with their own and normal procurement practices, has taken place.

12. The successful contractor, <redacted> had done considerable work at the academy prior to being awarded the school refurbishment work, we found 4 invoices totalling £32k. Initially it was thought that an invoice had been paid prior to the receipt of the quotes. The EHT thought there had been errors by the tendering companies in the dates of the quotes but has since stated that the successful company, <redacted>, dated an invoice incorrectly. The EHT has said that this is a small company and they have made mistakes with invoice dates previously. In addition a further quote from <redacted> was provided in relation to new window blinds, the quote was for £9,250.00 (ex-VAT), three subsequent invoices were submitted for this work, all of which were valued under £5k (ex-VAT)’.

At this point, those with ideological antipathy to academies no doubt will be crowing, and it has to be admitted that the facts as currently known are without doubt disquieting.

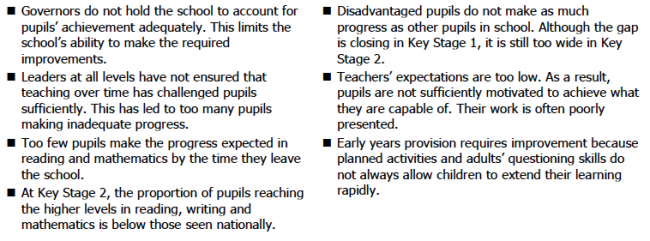

But delving deeper into the history of SBAT and its antecedence gives pause for further thought, because an Ofsted inspection of Longshaw Primary in February 2015 – that is, before the school joined SBAT, and still remained firmly under local authority control – rated it as ‘inadequate’, and came to these fairly scathing conclusions:

As is so often the case in Waltham Forest, residents are thus caught, forced to chose, it seems, ‘Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea’.