LBWF’s equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) programme: necessary corrective or self-serving extravagance?

In the past couple of years, and without much public commentary, the senior management team in LBWF has been seeking to transform the prevailing culture in the Town Hall by introducing and then championing a major equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) programme.

Specifically, the aim has been to ensure that:

(a) ‘our workforce reflects the diversity of our community’, on the basis that this will ‘lead to stronger connections with our communities and better design of services’;

(b) there is maximum ‘inclusivity’ so that ‘people feel safe to bring their authentic selves to work’;

(c) the work environment allows ‘everyone…to access good quality and suitable opportunities for learning, development and progression’; and

(d) pay is ‘fair and equitable’ for all, with ‘targeted approaches’ where necessary.

Overall, the impression given is that this is a unique opportunity to right entrenched wrongs; indeed, some management documents updating the rank and file have the dramatic heading ‘Your crisis, our action’.

What does all this mean in practice? The following are three of the programme’s central components.

Staff networks

LBWF states it has placed staff networks at the heart of the EDI programme because it believes they ‘connect our growing council by creating spaces for our staff to access support, guidance, and belonging’.

Currently, according to a Freedom of Information Act (FIA) response, there are four such networks, the Race Equality Network, the Women of Waltham Forest Network, the Out in the Forest Network, and the Carers Network.

Each receives £20,000 per year to spend as they wish, while the Race Equality Network was provided with an extra £20,000 ‘across 2021-23’ to support ‘large scale events during Black History Month and Culture Fest’.

Moreover, LBWF guarantees that staff involved in the networks have ‘protected time’, i.e., time off from their normal duties to use for network business, a beneficial arrangement previously only granted to trade union representatives.

The Equalities Board and targeted interventions

To oversee the EDI programme as a whole, LBWF has created a dedicated Equalities Board, composed of senior managers and members of the four staff networks, and this co-ordinates a growing number of interventions, an update of February 2023 illustrating the wide spectrum on offer:

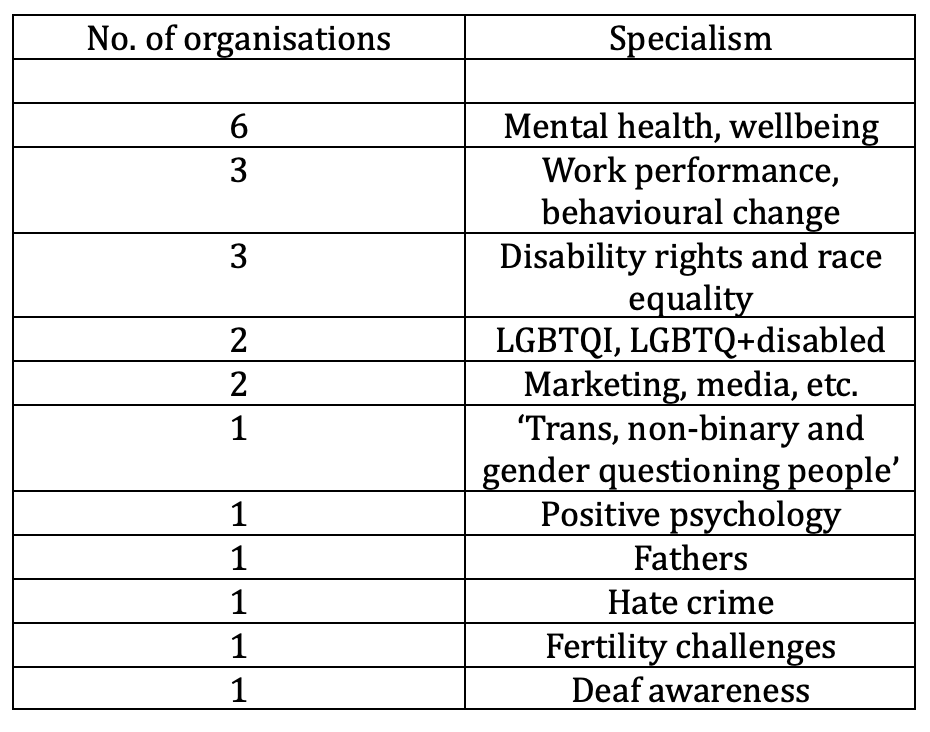

Some of these interventions are run in-house, organised by a team of well-paid EDI staff, but LBWF has also brought in 22 external delivery partners, their specialisms being as follows:

The cost of this outside help is opaque, but appears to be c. £139,000 in the period 2022-24.

Workforce Positive Action Policy

The Workforce Positive Action Policy (WFPAP) is designed ‘to enhance the Council as an employer of choice, with a diverse workforce at all levels, supporting people of diverse backgrounds [to] apply for our jobs, flourish and stay in our employ’.

The WFPAP states that ‘the principle of selection on merit is key to recruitment or promotion decisions, as it ensures the best people are in the right jobs to provide services to our residents’.

But it also observes that ‘Positive Action measures in recruitment and learning & development will be used where, as employer, Waltham Forest Council reasonably believes that people with a protected characteristic are under-represented in the workforce or within identified teams, or suffer a disadvantage connected to that protected characteristic’.

That sketches in the EDI programme’s organisation and content. How should it be judged?

Some of the foregoing appears eminently reasonable. After all, who doesn’t want fair treatment at work, or action to limit discrimination against, say, the disabled? The only slight surprise is that under the previous CEO, Martin Esom, shortcomings that are now thought grievous apparently were ignored.

But, the reasonable accepted, there are other parts of the EDI programme that are certainly controversial, and the latter can be grouped under the following headings.

The LBWF workforce and diversity

As already noted, one cornerstone of the EDI programme is the idea that LBWF staff should ‘reflect’ the diversity of the borough’s population, on the basis that such an objective is not only fair but also will lead to better policies.

Yet, cornerstone or not, careful research shows that in reality LBWF’s pursuit of what it often refers to as ‘greater levels of representation’ is surprisingly selective.

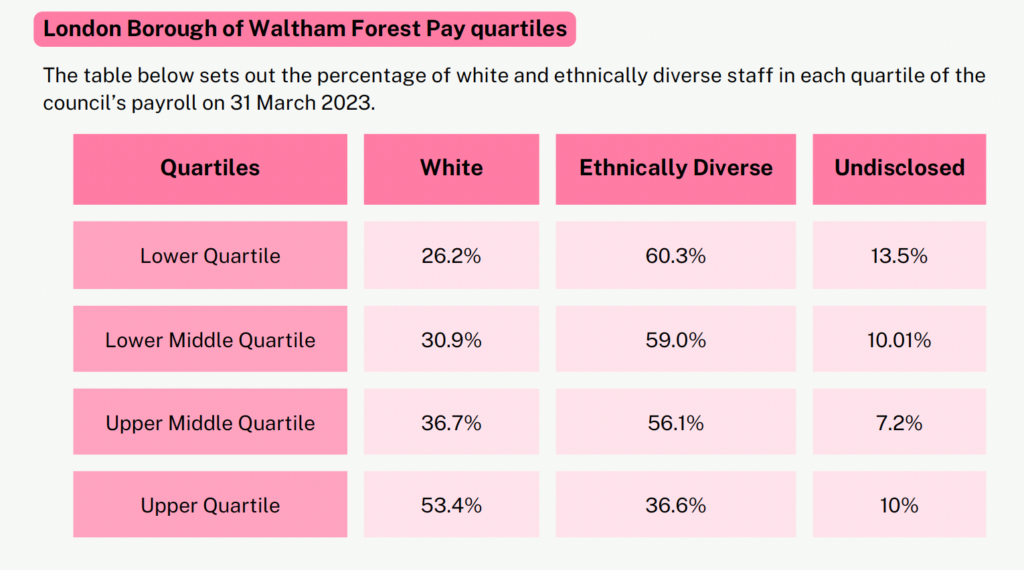

At the top of the organisation, the situation is fairly clear-cut. As LBWF sees it, the problem here is that ‘White’ men dominate, while ‘all’ ethnically diverse groups are underrepresented, as this table on pay quartiles seemingly demonstrates:

Accordingly, from the outset, LBWF has instigated corrective action, for example, according to one authoritative account, ‘sessions delivered by diversity and inclusion thought leaders on imposter syndrome, unconscious bias and microaggressions in the workplace’.

But further down the hierarchy, the same concern is less in evidence.

Publicly available data demonstrates that the make-up of the LBWF workforce below senior management level differs markedly from the demographics of the borough, with ‘women’ staff and ‘Black and Black British’ staff significantly overrepresented, and ‘men’ staff, ‘White’ staff, and ‘Asian British’ staff significantly underrepresented.

Nevertheless, despite its rhetoric, and the extent of these differences, in this instance LBWF seems loath to intervene.

Thus, when asked under the FIA whether it has any policies to address the underrepresentation of ‘men’ staff, ‘White’ staff and ‘Asian British’ staff, LBWF responds only that ‘There are no such policies relating to men and white staff given both groups are strongly over represented in the most senior, well paid roles in the Council’ – the sophistry about ‘men’ and ‘White’ staff, and the evasion about ‘Asian British’ staff, both eye-catching.

The lesson seems to be that LBWF likes to play the numbers game, but only when it suits.

Evidence

As might be imagined, the EDI programme has produced effusive comment and evidence.

But not all of this material is necessarily persuasive.

One problem is that a sizeable number of those who work in the Town Hall are loath to answer questionnaires. For example, the 2022 Your Voice Matters Staff Survey, which has greatly informed subsequent interventions, achieved a response rate of only 55 per cent.

Likewise, LBWF has struggled with low staff declaration rates for disability and sexual orientation, to the extent that in 2022, it admitted that ‘the Council’s current pay gap findings’ were ‘statistically unsound’.

In other cases, there is some doubt as to whether LBWF is really comparing like with like. The data on pay quartiles reproduced in the table above is a case in point. No allowance is made here for age or educational and professional attainment. Moreover, use of the broad-brush category ‘Ethnically Diverse’ disguises important differences between the various constituent groups that it aggregates, with national data showing that Indian and Chinese workers sometimes earn more than their White counterparts, and far more than, for instance, Bangladeshis.

Another example concerns LBWF’s gender pay gap. A great deal is made of this, and particularly the finding that ‘the proportion of women is much greater in lower paid roles where there are three times more women than men’.

But read the small print and it turns out that ‘Lower paid roles historically filled by men, such as street cleaning and refuse, have been outsourced and are not included in the council’s gender pay gap’, an admission that considerably qualifies the whole exercise.

Staff networks and accountability

Those with longer memories doubtless may be a little nervous about staff networks, because in past years local government as a whole was notoriously plagued by the Freemasons, a secretive organisation with its own hierarchy and agenda.

LBWF’s networks are, obviously, different in character, but doubts remain.

Little is known about how the networks function. Are they democratically organised? Do they have constitutions? How do they spend their money? And why is it that there seems to be little reference to any of this on LBWF’s website?

Then there is the issue of what the networks actually do. Most aim to provide ‘safe spaces’ for discussion and general mentoring, which seems unremarkable, but one or two appear to aim at influencing council policy as well, and that is more contentious.

After all, in the UK system, it is councillors who hold sovereignty, with regular elections ensuring their accountability.

Pressure groups have their place, needless to say, but surely those receiving public money should be required to operate openly and transparently, rather than, as is the case in LBWF, away from public scrutiny.

What’s left out

As noted, the EDI programme is multi-faceted, but there are some surprising omissions.

First, in law, ‘age’ is a protected characteristic, but older people in the Town Hall do not have a staff network, and age discrimination is rarely discussed, even though LBWF admits that ‘Employees aged 60 and over are under-represented in higher grades’, a finding that in other cases would be thought damning.

Second, while the EDI programme readily classifies staff by ethnicity and/or sexuality, it completely overlooks social class, inexplicable as this is known to shape, for better or worse, many important life outcomes.

Thus, taking EDI strictures at face value, an ‘Asian British’ staff member from a high caste, who has been privately educated and then attended Oxbridge, will be eligible for special support even despite these advantages, because of being from an ‘underrepresented’ ethnicity.

Of course, in practice (for example when interviewing for promotion, etc.) class, or at least aspects class, may be brought into the mix.

But then why isn’t that explicitly recognised in the WFPAP, so it is clear to all concerned?

Third, though the EDI programme trumpets the importance of diversity at every opportunity, there is virtually no mention of ‘diversity of thought’, and revealingly when LBWF recently was asked under the FIA whether it has run ‘courses, seminars, or similar, focusing on the legal basis and importance of freedom of speech, both in the Town Hall and in relations with residents’, it replied that it hadn’t.

EDI and residents priorities

Finally, LBWF claims that the EDI programme will lead to ‘stronger connections with our communities’ but whether this is true or not is again debatable.

It is noticeable, to begin with, that LBWF’s explanation of exactly how this happy outcome will occur is sketchy. It appears to believe that EDI interventions will deliver staff with a wider array of ‘lived experiences’, making the Town Hall policies ‘better designed’, while at the same time bolstering relations with residents from different backgrounds who now ‘see themselves in the Council’.

Both these outcomes are theoretically possible, but there are important caveats. Currently, two thirds of LBWF staff choose to live outside the borough, and, EDI interventions or not, that means their pertinent ‘lived experience’ will always be only partial. And while it is true that some residents may be pleased to find that there are council staff who resemble them in terms of ethnicity or sexuality, there is no available evidence that suggests this is anything like a major preoccupation.

On the contrary, what most residents of all kinds tend to focus on are – predictably and understandably – everyday perennials like value for money, rent levels and service charges, council tax, refuse collections, and recycling.

And, crucially, what they want is for LBWF to respond to inquiries and complaints about these issues proficiently, something that a large number do not believe happens now, the then LBWF head of media, Eddie Townsend, in fact admitting at a Local Government Chronicle roundtable in June 2024: ‘“The more people come into contact with the council, the less satisfied they are”’.

To conclude, it’s worth noting that – amusingly – while LBWF has been eagerly adopting the DEI approach, many other government departments and corporates in the UK have been dropping it, on the basis that, when properly evaluated, EDI interventions often turn out not to work very well (unconscious bias training being a good example, see links), and may actually prove divisive.

In this context, it will be interesting to see for how long LBWF is willing to resist the tide.

On the one hand, those most involved in running the programme inside the Town Hall will likely fight hard against any roll back, not least because they currently enjoy a degree of status compared to their colleagues, plus material benefits (including time off work and access to an exclusive career ladder) which they would otherwise be without.

But on the other hand, the LBWF leadership no doubt will be acutely aware that, when staff time is factored in, the EDI programme is fairly expensive; that overall, there is less and less money available to play around with; and that in some service areas, as recent scandals show (see links), performance on the ground is so poor that it makes worrying about whether residents ‘see themselves in the Council’ look both irrelevant and self-indulgent.

It’s apparent, then, that the LBWF leadership is caught between a rock and a hard place.

Watch this space.