LBWF’s Violence Reduction Partnership aims to reduce knife crime, but after 5 years, £6.6m. of funding, and only disappointing results, it urgently needs a re-think

In the middle years of the 2010s, there was escalating public disquiet in Waltham Forest about violent crime, particularly knife crime involving local youth, with newspaper reports focusing on both the volume of offences and the fact that the only a small number of perpetrators were being prosecuted (see links, below).

Accordingly, in November 2018, and largely as a response, LBWF launched a Violence Reduction Partnership (VRP), comprising its own staff and representatives of the police, schools, the heath service, the voluntary sector, businesses and the wider community, in order ‘to tackle violence and its root causes’, with, it was emphatically stated, ‘the wellbeing of young people at the heart of its ambitions and solutions’.

What follows sketches in the subsequent development of the VRP, and then assesses its impact.

The VRP has adopted what it calls a public health approach to violence, which is ‘structured around’ four ‘domains’, described thus:

‘Curtail – strong enforcement which seeks to predict, disrupt and tackle specific acts of violence, and prosecute and rehabilitate perpetrators.

Treat – quick, effective, trauma-informed treatment for anyone who has experienced violence.

Support – early, targeted support for those most vulnerable to violence and exploitation, to reduce the risks they face.

Strengthen – widespread empowerment of communities to build resilience and prevent violence’.

Turning to the VRP’s practicalities, LBWF has looked after finance and the day-to-day management of the programme, while hiring in partners to deliver on the ground, and these provide, amongst other things, mentoring, life skills, outreach work, support for parents and carers, diversionary activities, and stop and search advocacy.

As to what all of this has cost, according to a Freedom of Information response, the VRP spent £6.6m. between 2019-20 and 2023-24, with LBWF contributing about a third of this sum, and the rest coming from the Mayor’s Office and NHS England.

Has the VRP made a difference?

Answering this question accurately is more difficult than might be imagined. Not unexpectedly, senior Labour councillors initially asserted that the VRP was both pathbreaking and already delivering strong results, but the reality is that subsequently LBWF has not published much systematic information to back up these claims.

To illustrate, though LBWF produced an annual report at the end of the VRP’s first year of operation, nothing similar, as far as can be ascertained, has followed.

Furthermore, for reasons that are unexplained, LBWF has not appointed an external partner to regularly review the VRP’s progress, despite the fact that it used this kind of safeguard previously with its long-running and closely related Gang Prevention Programme (see links, below).

Luckily, however, there are some other helpful data sources, the most important being the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) series on knife crime offences in London, which is broken down by borough.

Reviewing the VRP at the end of 2019, Cllr. Ahsan Khan, then Cabinet member for Community Safety, was upbeat, observing that, for Waltham Forest, ‘The most recent statistics are promising – a 27% reduction in knife crime offences over 12 months’.

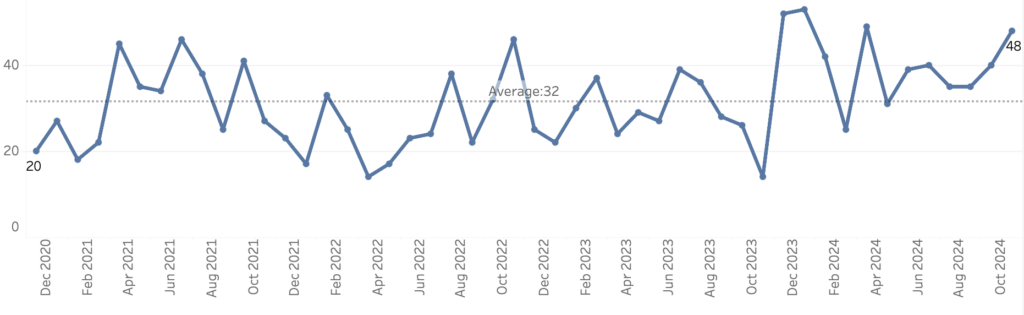

Yet the MPS figures for the following years (now collected on a slightly different basis) are far less positive, and show that, while knife crime offences have fluctuated month by month around the average, overall there is no sustained downward trend:

Number of knife crime offences in Waltham Forest, November 2020 to October 2024

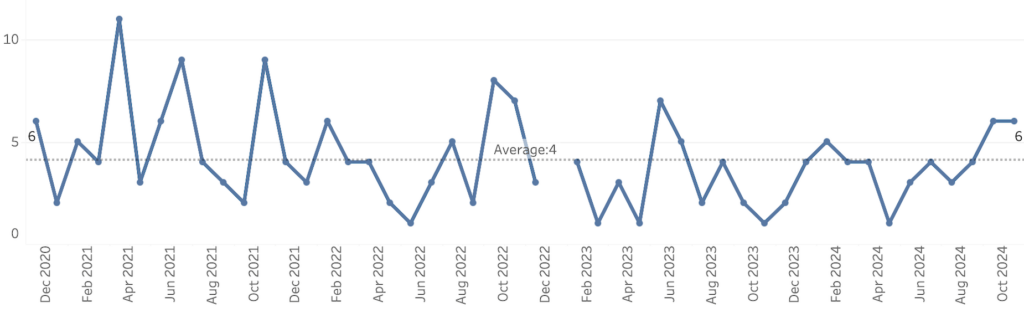

Equally concerning is that fact that few knife crime offences have resulted in what the MPS calls a ‘positive outcome’, meaning that a perpetrator is identified and charged or otherwise sanctioned:

Number of knife crime offences in Waltham Forest that have resulted in a ‘positive outcome’, November 2020 to October 2024

To summarise, taking the period November 2020 to October 2024 as a whole, there were 1,518 knife crime offences in Waltham Forest, but only 192 ‘positive outcomes’, suggesting that in about 85 per cent of cases no-one was caught, let alone punished.

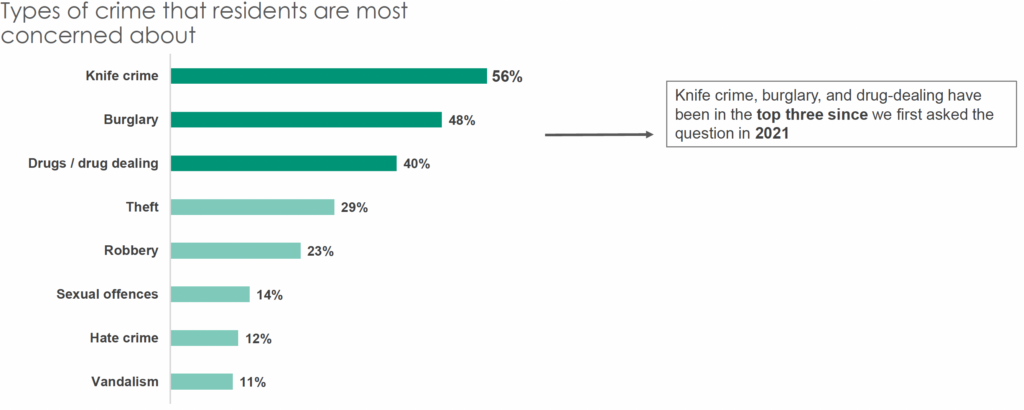

Another data source that is relevant to an assessment of the VRP is LBWF polling about which crimes residents are most concerned about.

Predictably, given LBWF’s obsession with spin, the results of this polling are rarely made public, but a slide dated Spring 2023 presented to its Citizens Assembly gives a flavour of the past few years’ findings:

It would appear, therefore, that the VRP has done little to dent the popular unease about knife crime that led to its creation in the first place.

What explains these apparently disappointing outcomes?

Needless to say, dealing with knife crime is no easy matter, and given that gangs have become well embedded in the borough’s social fabric, and drug-taking is so rife, some level of violent criminality is virtually inevitable.

But this unhelpful context accepted, the VRP leadership’s way of working may have made the situation worse than it needed to be.

Take monitoring. Clearly, in any programme of this type, it is vital that delivery partners achieve their agreed targets, and this means ensuring that they regularly submit performance data, so that, if necessary, corrective action, up to and including dismissal, can be taken.

Yet with the VRP, such a rigorous approach seems to have been intermittent rather than routine.

For example, a data summary document of September 2023, released under the Freedom of Information Act, shows wide differences in the way that the ten delivery partners then involved were allowed to report their results, with some submitting detailed statistical returns, and others submitting almost nothing at all.

In addition, there is evidence of wider failings. Questioned about the VRP, also in 2023, delivery partners not unexpectedly rated their own contributions highly but were critical of the organisational framework in which they operated.

Amongst the ‘gaps and issues’ which they cited were the following:

‘Resources not adequately targeted

Lack of long-term coordination

Some service/provisions available at schools are missing at colleges

Providers/services need…[an] idea of where they sit in the context of the wider VRP

A better focus on preventative work

A need for up to date data for the VRP’.

In conclusion, the VRP unarguably has not been the game-changer as originally envisaged.

For that reason, it is surely time for a re-think. Perhaps the VRP needs a new and more demanding leadership team, a leadership team that, for example, continually evaluates outputs, and only allocates money when it is deserved?

Perhaps that leadership team, too, needs to be more transparent, and publish the details of what’s going on?

Perhaps it’s even time to reassess the much vaunted public health approach? For instance, has the VRP got the balance right between worrying about the ‘root causes’ of crime and catching criminals?

One condition though. This re-think can’t be left to council officers and organisations with vested interests, but must involve ordinary residents, because it is they who live with the scourge of knife crime, so it is they who should have a big say in how to deal with it.