New official data shows that seven years after Grenfell nearly all LBWF housing blocks have ‘life-critical fire-safety defects’, leaving tenants to live with the risks

In 2020, after LBWF was involved in several notable fire safety scandals, including the purchase of hundreds of misleadingly labelled fire doors, the subject of a fraud inquiry, it began a programme of remedial work to bring its housing stock ‘up to the most modern…safety standard’, this being forecast to cost about £40m., with the final sum dependent on what was discovered as the work proceeded.

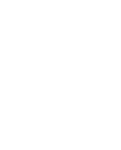

The following year, officers updated the Audit and Governance Committee about progress in January and October, the focus being on the number of remedial actions that had been either completed or were outstanding:

As can be seen, the proportion of actions which were outstanding had fallen slightly over the ten month period, from 45 per cent to 41 percent, but ominously the total number of actions which were said to be required had increased, and by a significant 13 per cent.

Thereafter, this programme largely disappeared from public view, with the Audit and Governance Committee, puzzlingly, never returning to the subject.

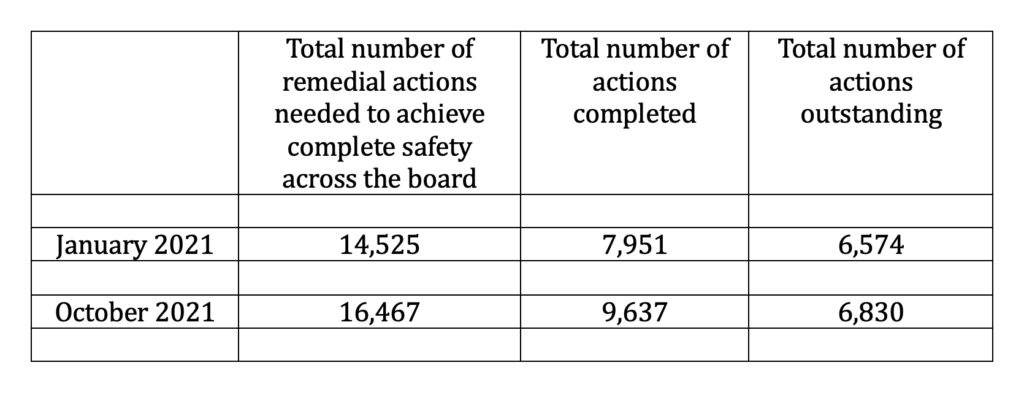

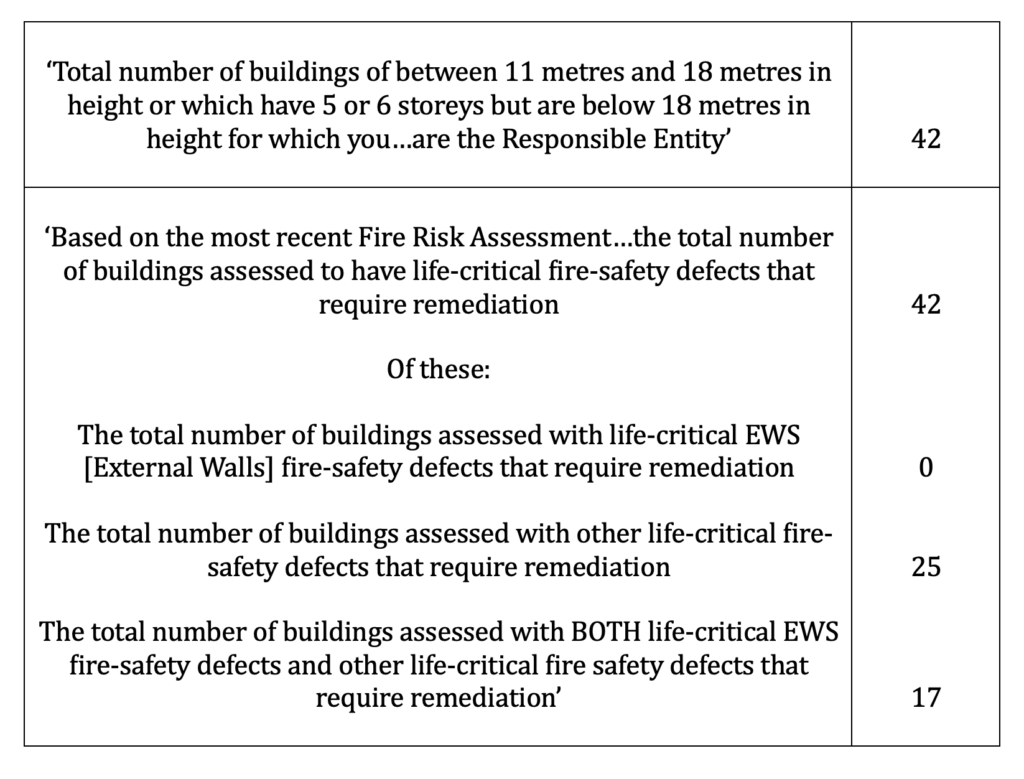

However, from September 2023, the newly created Regulator of Social Housing (RSH) has required all social housing providers to make quarterly returns about the fire safety of their housing stock, both low-rise blocks (‘Buildings of between 11 metres and 18 metres in height or which have 5 or 6 storeys but are below 18 metres in height’) and high-rise blocks (‘Buildings of at least 18 metres in height or which have at least 7 storeys’), and these returns cast new light on how matters stand with LBWF.

The picture that emerges is a shock, because it is so disconcerting.

The most recent return, dated 25 June 2024, can be summarised in the following two tables, the first focusing on low-rise blocks, the second on high-rise blocks:

So, in short, as of a few months ago, LBWF admitted that

- 62 out of its 63 low-rise and high-rise blocks were blighted by ‘life-critical fire-safety defects’;

- and, in nearly half the cases, these defects encompassed both internal issues (such as ‘fire stopping works’, ‘fire door improvements’, and ‘signage’) as well as problems with the external walls.

Two further revelations increase the sense of unease. First, LBWF disclosed in its June 2024 return that ‘barriers’ might cause ‘variation’ to its remediation plans, and described these barriers as ‘Additional works found while on site i.e [sic] timber packing for windows and asbestos’ [emphasis added], the latter material, as far as can be ascertained, not publicly mentioned before in this context.

Second, reading through some correspondence released under the Freedom of Information Act gives the impression that, from the outset, LBWF has continued to struggle with the RSH’s new reporting regime, on occasion failing to understanding what information must be submitted, forwarding figures that are nonsensical, or having to be cajoled into meeting deadlines, none of which inspires confidence.

Seven years have passed since Grenfell, and more than four years since LBWF started remediation work on its housing stock.

That almost all of its blocks are still not fire-safe is disgraceful.

LBWF happily spends time and money pandering to big private property developers and financing associated schemes to attract affluent incomers, from the £700,000 recently used to smarten up Walthamstow’s Blackhorse Beer Mile, to the tens of millions spent on Mini-Holland.

But when it’s a case of its own tenants facing tangible risks, that’s clearly a different matter entirely.