Air quality in Waltham Forest: Cllr. Loakes focuses on emissions, but new figures show particulate matter is a big killer, too, and LBWF seems slow to recognise that

In the Summer 2024 issue of the council’s Waltham Forest News, Cllr. Clyde Loakes MBE, Deputy Leader and Cabinet Member for Climate and Air Quality, reports: ‘“Waltham Forest has the lowest per capita emissions in London bar one and I’m incredibly proud of what we’ve achieved so far alongside local communities and businesses”’.

This is perplexing for a couple of different reasons.

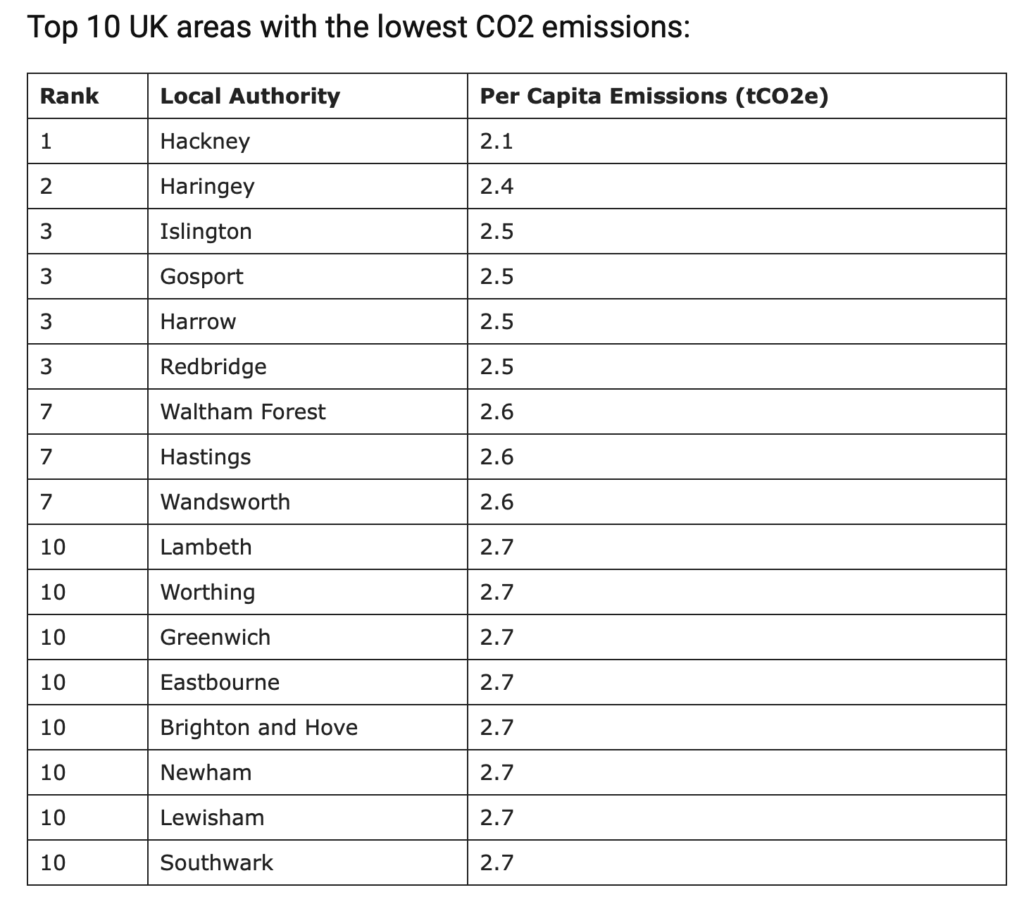

First, the reality is that Waltham Forest’s status as a low emissions borough is nothing new. In 2023, for example, Energy Manager Magazine published this table:

In fact, between 2005 and 2012, that is the seven-year span immediately before LBWF began work on Mini-Holland and associated schemes, Waltham Forest was always one of the top three London boroughs with the lowest per capita emissions.

Second, it is also true, as the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero points out, that in historical terms London has long enjoyed the lowest per capita emissions of any UK region (due to ‘the urban nature of the transport system, a higher population density and its lower level of large industrial facilities’), while per capita emission figures have been steadily improving, not just in Waltham Forest, but right across the capital.

Cllr. Loakes’ claim, therefore, seems rather odd, perhaps even an exercise in smoke and mirrors.

This conclusion is thrown into sharp relief because while Cllr. Loakes has been drawing attention to emissions, another data set about air quality has been released which is far more alarming.

Particulate matter (PM) is a term used to describe the mixture of solid particles and liquid droplets in the air. PM can be naturally occurring, but is also produced during the combustion of solid and liquid fuels, such as for power generation, domestic heating, and in vehicle engines. It varies in size. One often measured type is PM2.5, particles with a diameter generally less than 2.5 micrometres.

And the reason why PM2.5 has attracted attention stems from the fact that such particles are dangerous, as they can enter the blood stream and have serious consequences.

Thus, the Greater London Authority advises: ‘Based on current evidence, PM2.5 is thought to be the air pollutant which has the greatest impact on human health. Both short and long-term exposure to PM2.5 increases mortality risk from lung and heart diseases and stroke as well as increasing hospital admissions’.

Turning to the situation with PM2.5 in Waltham Forest the news is not good.

For figures recently released by the government’s Office for Health Improvement and Disparities show that, as of 2022, the impact of PM2.5 air pollution in Waltham Forest, expressed as ‘a percentage of annual deaths from all causes in those aged 30 and older’, while still below pre-Covid levels, was nevertheless greater than in all but 12 of the other 150 English local government units (counties and boroughs).

Clearly, this is a worrying finding, and so it’s worth briefly turning to explore what may be its causes.

One possibility is that Waltham Forest is subject to greater amounts of PM2.5 than is normal elsewhere.

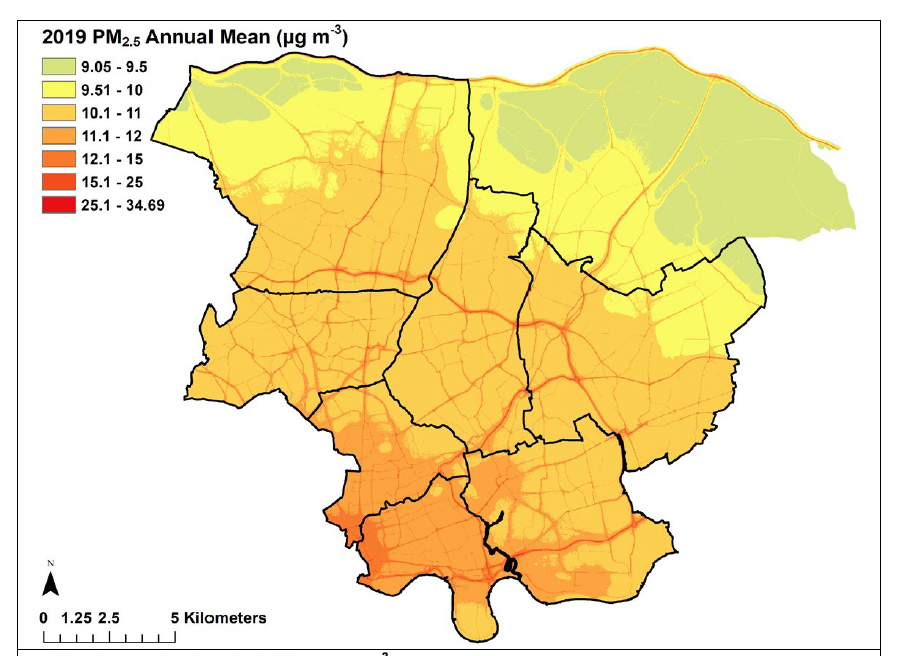

Establishing this definitively one way or another is beyond the capability of this blog, but a comparison with some immediately neighbouring boroughs, modelled for LBWF by the Environmental Research Group (ERG) at London University’s Imperial College in 2024, is perhaps indicative:

In short, Waltham Forest, in the centre of the map, does not seem to be particularly badly afflicted.

Another possibility is that LBWF has been caught on the back foot about PM2.5, and has failed to sufficiently recognise its threat.

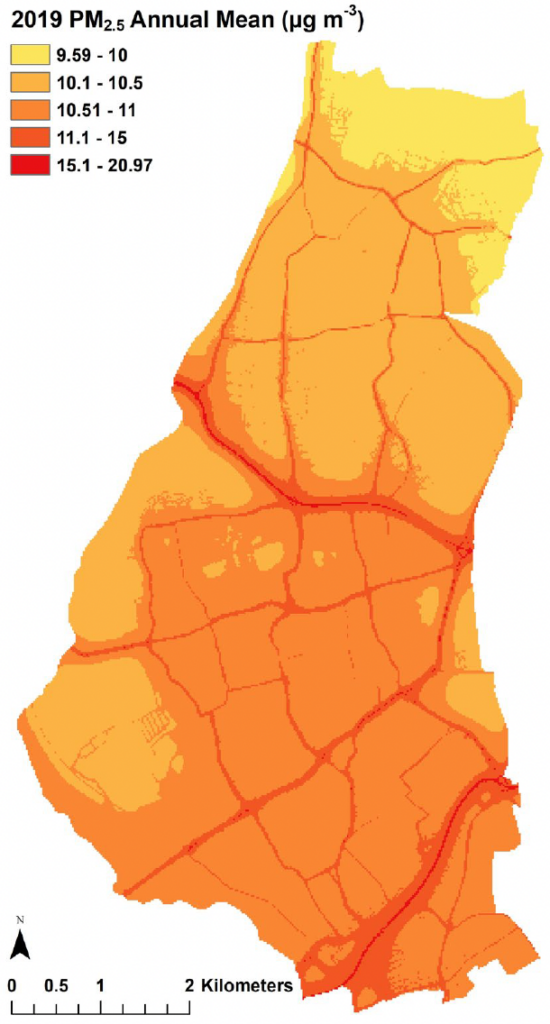

The evidence here is mixed. Another of the ERG models for LBWF, showing where PM2.5 was most prevalent in Waltham Forest as of 2019, reinforces the wholly unsurprising point that the worst concentrations are near main roads, and more generally, across the poorer wards in the borough’s south:

Yet though LBWF has carried out air quality monitoring for some years, the latest available Air Quality Annual Status Report reveals the fairly amazing fact, given the health issues involved, that only one of the council’s 64 monitoring sites – Dawlish Rd. in the back streets of Leyton – is actually set up to measure PM2.5.

The final possibility is that LBWF is well aware of the PM2.5 issue, and in fact has reacted with policy innovations, but these are not working.

Again, this is a very big subject, and one where it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between truth and spin (see links for the latter).

LBWF will no doubt point to the fact that it has spent £30m. plus on the aforementioned Mini-Holland and associated schemes, precisely because they will encourage a turn to public transport, cycling and walking, and thus limit motor vehicle emissions, including PM2.5.

However, whether in practice this objective is being achieved remains unclear. To give one example, LBWF intermittently promotes stories about women and ethnic minorities who are said to be taking up cycling, in order to give the impression that cycling is a universally popular activity, not just the preserve of middle-class men.

Yet when asked directly in 2023 who was actually cycling in the borough, and how often, LBWF admitted it didn’t have the data (see links).

Given all this uncertainty, it is reasonable to suggest that, to understand why PM2.5 is so damaging to local residents, LBWF now should turn away from studies produced by academics with their arcane deliberations, and contract a team of epidemiologists to address the issue anew, using the the statistics provided by the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities as a starting point, and then working back to identify first causes and then solutions.

PS I am grateful to Trevor Calver for bringing some of the evidence cited above to my attention.