LBWF’s new core strategy, ‘Mission Waltham Forest: our plan for a more equal borough’: laudable response to austerity, or cynical political opportunism?

At its February meeting, the Council approved ‘Mission Waltham Forest: our plan for a more equal borough’ (hereafter MWF), comprising a new ‘strategic ambition’ and ‘core purpose’, which is to make Waltham Forest a more equal borough by 2030, plus a new and ‘radical’ way of working, very much ‘a break from… business-as-usual’.

In detail, MWF will focus council effort and resources on ten different priorities, six about ‘the issues that matter most to our residents’ (homes, health, access to services etc.), and four about ‘how we must transform how we work if we are to deliver on our vision for the borough’.

Throughout, it is underlined, the emphasis will be on involving and listening to residents, with the same mantra repeated again and again: ‘Residents are at the heart of everything we do. We are determined to be a Council that listens to and works for everyone because our residents deserve an exceptional experience’.

All of this appears at worst uncontroversial, at best laudable.

But a closer look reveals a less rosy picture.

First, it is worth asking why LBWF has opted for MWF at this particular juncture.

To repeat, LBWF presents MWF as pathbreaking.

Yet just one year previously, LBWF had espoused another and very different ‘core purpose’, called ‘15 Minute Neighbourhoods: Our Corporate Framework’ (hereafter 15MN), which it also accompanied with various bombastic claims (‘We’re leading a local revolution on the streets of Waltham Forest’).

Moreover, like MWF, 15MN was all embracing, and involved significant expenditure, with, amongst other things, a well-known consultancy, the Young Foundation, contracted to report and advise; the appointment of a new Cabinet member, paid a yearly allowance of £39,304, to oversee progress; a glossy 29-page brochure; a promotional YouTube film; and a PR campaign to attract local and national media interest.

The Leader, Cllr. Grace Williams, even publicly pledged that £500 million would be spent on associated projects over the following five years in order to ‘“bring the plan to life”’.

So, in adopting MWF, LBWF has set aside a policy that it had previously asserted was absolutely crucial for the borough’s future, and also implicitly accepted that the sums spent on setting it up, possibly even some of the related projects, will have to be written off.

LBWF’s explanation for its change of direction is that ‘the intensification of a number of interrelated challenges, in particular the scale of the pressures the Council faces due to increased costs and demand’ make it unavoidable.

However, LBWF Leaders have been complaining about financial pressures for at least a decade, to the extent that today it is difficult to discern what’s true and what’s said for dramatic (and self-serving) effect.

Furthermore, it is not credible to suggest that there has been some enormous change in LBWF’s circumstances during the last 12 months.

So, in short, the justification for MWF remains unconvincing.

Close examination of MWF’s substance, too, is not reassuring.

First, what LBWF means by equality/inequality remains unclear. Is it trying to achieve equality of opportunity or equality of outcome? Or is it trying to achieve the homely, if fuzzy, formulation that it at one point references, a borough ‘where everyone can make the most of their strengths to live the life they want to lead’?

Relatedly, though there is reference to ‘barriers’ which are apparently holding people and companies back from ‘the life they want to lead’, there is little explanation of what these barriers are, and pointedly, words like ‘class’ and ‘discrimination’ are conspicuous by their almost total absence.

Second, there are signs of overreach. For example, one of the MWF missions is to ‘Build an economy that works for everyone’, encompassing, amongst other things, ‘decent jobs and services needed for underserved communities’, and ‘ambitious employment, training, and apprenticeship opportunities’, but the reality is that councils of whatever political complexion have only very limited powers to achieve such goals.

Moreover, LBWF’s track record here is anyway unimpressive. Between 2008 and 2013, a period when resources were abundant and staff plentiful, LBWF ran Worknet, a £8-9m. programme to help young people into employment, but many of the stated targets were missed, and there were credible accusations of fraud.

And though the Construction Training Academy in Cathall was described at its launch by the then Leader, Cllr. Chris Robbins, as ‘“a fantastic, world-class training facility for local residents and people from across east London”’, the intake from Waltham Forest has rarely, if ever, reached the levels originally promised (see links below).

Similarly, when LBWF has attempted to directly stimulate the local business community, what sticks out are its failures.

For instance, the LBWF sponsored E11 Business Improvement District (BID) Co. was involved in several serious controversies, and eventually collapsed in ignominy; while North London Ltd., which aspired to be ‘the sub-regional business support agency for North London’, received multiple council grants but achieved only patchy results, and was later revealed to have been audited by a firm where its company secretary was a director, earning an Institute of Chartered Accountants rebuke and fine (see links below).

Finally, regarding the ambition to ‘put residents at the heart of everything we do’, this seems to be uncomfortably close to pie in the sky.

One important point to remember is that LBWF has made similar promises on many occasions previously, yet conspicuously failed to deliver.

LBWF’s shortcomings have been most visible in its treatment of poorer residents. In fact, hardly a week has passed over recent years without social media or the press reporting a case of institutional indifference, perhaps downright unhelpfulness, where it’s less ‘listen’ and ‘involve’, more ‘ignore’ and ‘instruct’.

Indeed, when in February 2023 the Housing Ombudsman found LBWF guilty of ‘severe maladministration’ in dealings with tenants, including those struggling with damp and persistent anti-social behaviour, the sad truth is that it came as no great surprise (see links below).

But it’s also clear that attitudes found more generally in the Town Hall are often equally uncompromising, as a couple of examples demonstrate.

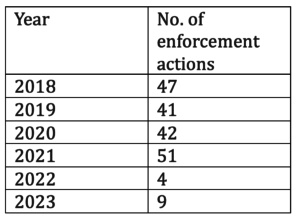

The enforcement of planning controls is, needless to say, vital, especially when structures that blight neighbouring properties are built without permission, or when landlords resort to illegal practices like renting beds in sheds and overfilling multi-lets.

However, enforcement action in Waltham Forest has fallen off a cliff edge:

Worse, when residents complain about this, they are told that nothing can be done since LBWF doesn’t have enough suitably qualified officers, though no explanation is offered as to why this sudden and dramatic shortage has occurred in such a brief period of time.

The way that LBWF responds to inquiries tends to be just as unsatisfactory.

A recent council survey found that 40 per cent of those who contacted the Town Hall were ‘not happy with the way their query was handled’.

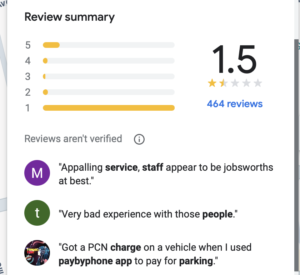

Other sources corroborate. Thus, Google reviews are almost entirely adverse, with many complaining that, when they contact the Town Hall, it is difficult to reach the right person, never mind resolve an issue:

Clearly, LBWF hopes that, with the turn to MWF, the treatment of residents will improve, but this overlooks some stark realities.

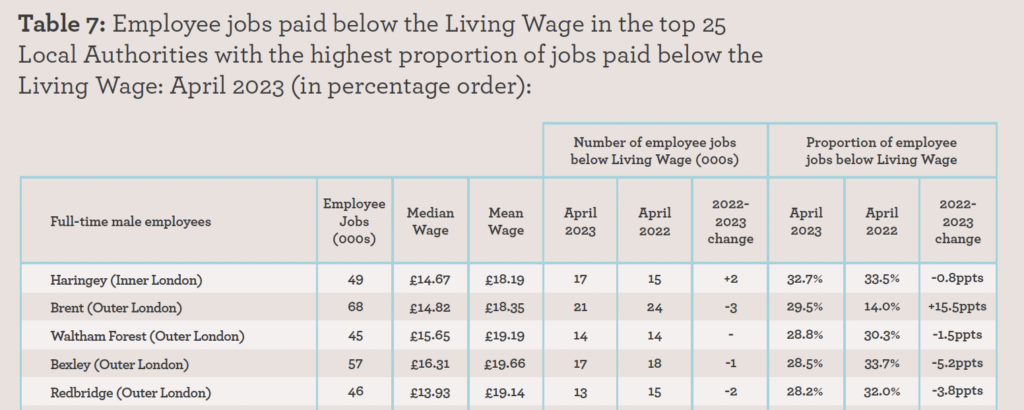

According to the Living Wage Foundation, LBWF employs an unusually high proportion of low waged staff, and is rated third of the worst offending 25 local authorities in this league table of shame:

That alone is indicative of a management which places insufficient value on its workforce, but the clincher is evidence that emerges from a 2023 staff survey.

Because this reveals that many of those responding did not have much idea of the council’s strategic direction; only a minority believed ‘the learning and development opportunities they have access to are helping them to develop their career’; while ‘a clear area for attention’ was ‘employee voice and staff feeling able to speak up’, with the following paragraph elaborating:

‘Just 42% of staff feel it is safe to speak up and challenge the way things are done at the Council, which is 20% points below the local authority benchmark. In addition, improving management (e.g. support and listening to staff) was the most common theme provided in the open text comments. This issue also came through strongly in the qualitative feedback, with staff experiencing micro-cultures of poor top-down communication on decision-making, as well as poor collaboration and consultation with managers and leaders’.

With these findings in mind, it is reasonable to conclude, first, that a major impediment to ‘putting residents first’ is the fact that a large number of Town Hall staff are badly paid, poorly treated by their managers, demoralised, and as a result only partly engaged; and, second, that turning this around will be much easier said than done, not least because it will only be possible with considerable expenditure, nowadays frankly unlikely.

To sum up, much of LBWF’s commentary about MWF should be taken with a large pinch of salt. In fact, contrary to the narrative presented, the suspicion grows that MWF may be in essence most about the quest for political advantage, with the equalities banner being wheeled out first because it sugars the pill of Town Hall redundancies and upcoming service cuts, and second because it allows the council leadership to project itself as standing on the moral high ground.

It is scant consolation for residents that, in a few years’ time, MWF no doubt will be forgotten, because by then, on current form, LBWF probably will have completed at least one further expensive re-brand…possibly even two.