The Information Commissioner’s Office audit of LBWF: less a forensic examination, more a damp squib

The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) has just released the executive summary of a ‘Data protection audit report’ focusing on LBWF (ICO policy, apparently, is not to release the full version).

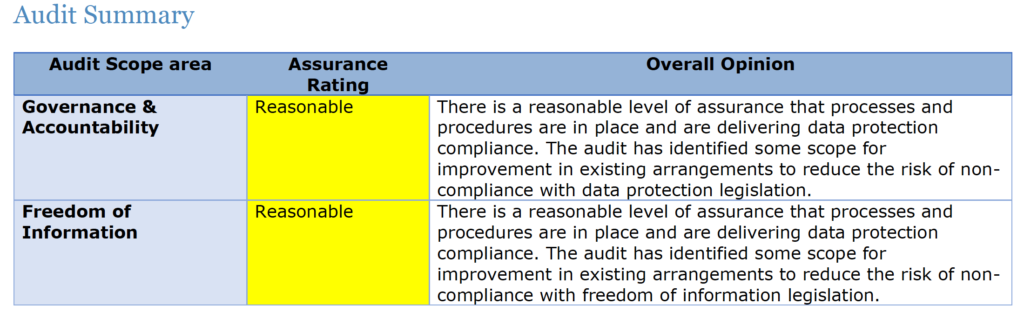

The ICO’s overall judgement is that, as regards both the governance and accountability of data protection and the operation of the Freedom of Information Act, LBWF is achieving ‘a reasonable level of assurance’:

However, whether the ICO’s assessment is credible remains questionable, as the following paragraphs demonstrate.

First, it’s worth noting that the ICO itself draws attention to some of the audit’s limitations.

As might be expected, the pandemic has imposed constraints. Site visits to inspect records were impossible, and in the end, the ICO had to be content with ‘[a] desk based review of selected policies and procedures and remote telephone interviews’.

Furthermore, the ICO adds, the ‘scope of the audit’ was partly shaped by LBWF itself, with the approach taken described as ‘consensual’.

Turning to the ICO’s substantive findings, what emerges, somewhat surprisingly, is that many appear to be at odds with its benign overall assessment.

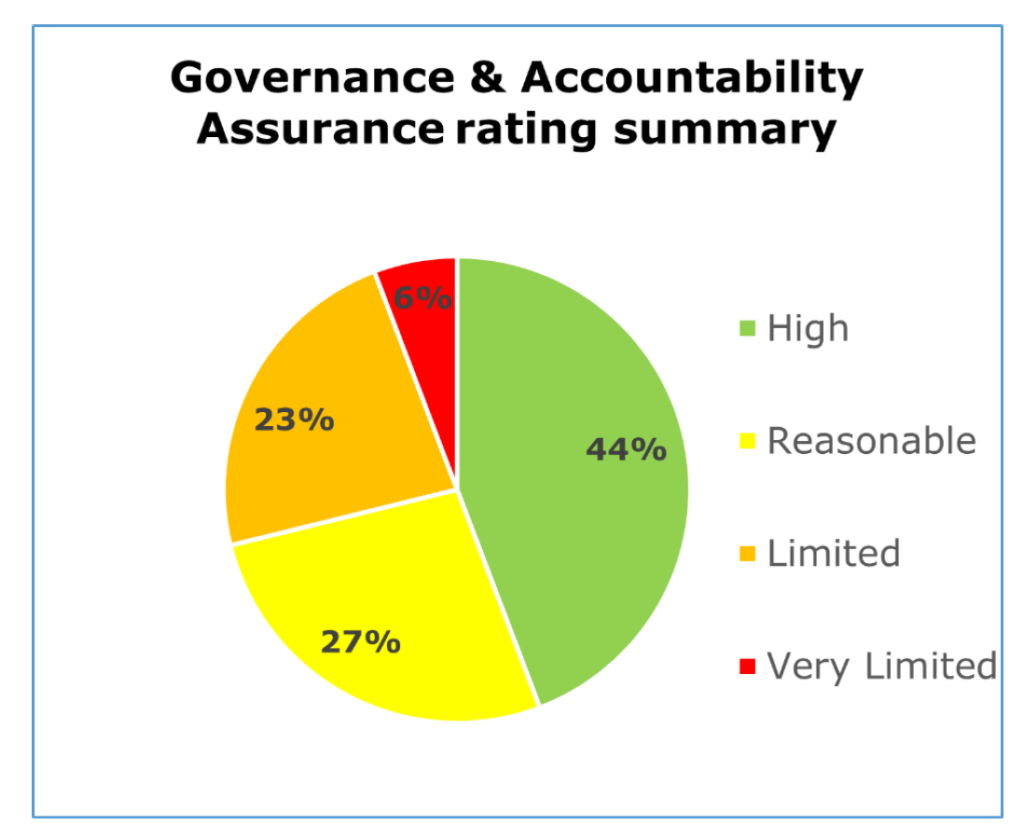

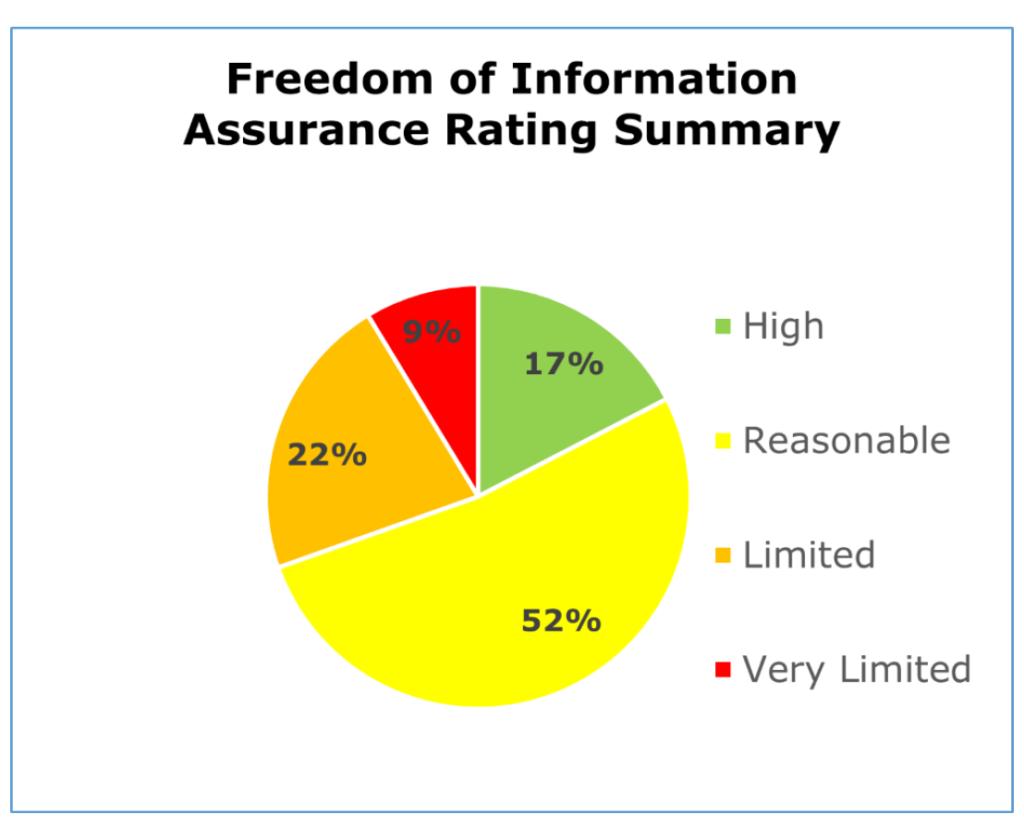

For example, two pie charts show how the data protection and Freedom of Information Act service areas are doing in terms of ‘assurance ratings’, obviously a key metric:

There is no explanation as to which particular indicators are being measured here, but it is surely shocking to find that, across the board, assurance in roughly 30 per cent of the constituent cases is either ‘limited’ or ‘very limited’.

The ICO’s 38 recommendations give a similar impression, since 18 – nearly half – are classed as either ’urgent’ or ‘high’ priority.

Indeed, it’s clear that LBWF is still a long way from even moderately acceptable practice.

For instance, the ICO notes:

‘LBWF does not currently report KPIs [Key Performance Indicators] on its compliance with subject access requests or records management obligations. By not monitoring this data LBWF lacks oversight and assurance that it is in compliance with its statutory obligations. LBWF should begin capturing and monitoring this data on a routine basis’.

In addition, the ICO believes that LBWF should change the way it handles data protection issues as a whole, in order to ensure that the current Data Protection Officer, Director of Governance and Law Mark Hynes, avoids any ‘conflict of interest’ (though regrettably the latter point is only mentioned, not explained).

As many people will justifiably ask: if this amounts to a ‘reasonable level of assurance’, what on earth does an ‘unreasonable level of assurance’ look like?

However, taking one step back reveals that the ICO’s rather emollient approach in this case is very much in keeping with a by now well-established pattern.

The ICO had been aware of LBWF’s failings over data protection and the Freedom of Information Act for some years, and in 2020 finally issued the latter with a ‘practice notice’ because it was making ‘errors’ of an ‘over-arching procedural nature’, in particular failing to comply with five sections of the relevant Cabinet Office guidance document – ‘Part 1 – Right of Access, Information; Part 1 – Right of Access, Means of communication; Part 4 – Time limits for responding to requests; Part 5 – Internal reviews; [and] Part 6 – Cost limit’.

That sounded promising. But subsequently, though local residents’ complaints show time and again that LBWF is still offering the same poor service, little further regulatory action has followed.

Quite why the ICO is so supine remains unclear, though some believe it has become over concerned with the pursuit of high profile cases and thus headlines.

Whatever the truth, it’s clear that the ICO’s current attempt to coax LBWF forward is leading nowhere fast.

The blunt fact is that LBWF only ever changes when forced to.

And that is a lesson the ICO now needs to learn – and fast.