LBWF councillors right to withhold ‘sensitive’ information about themselves on the Register of Interests: use and possible abuse

Though relatively rarely discussed, a clause in the current local government legislation allows councillors to withhold information on their register of interests forms so long as the monitoring officer agrees the information in question is ‘sensitive’, meaning, if made public, would lead to ‘violence or intimidation’ either directly or against ‘a person connected’.

The reasoning here is fairly obvious. Councillors are a vital part of local democracy, and must be allowed to carry out their public duties free from fear. Moreover, if abusive behaviour is allowed to flourish, it may well deter members of the public from seeking office in the future, and thus pose a significant threat to the continuity of the system as a whole.

So how many LBWF councillors have petitioned LBWF’s Monitoring Officer, Mr. Mark Hynes, and been granted this kind of protection?

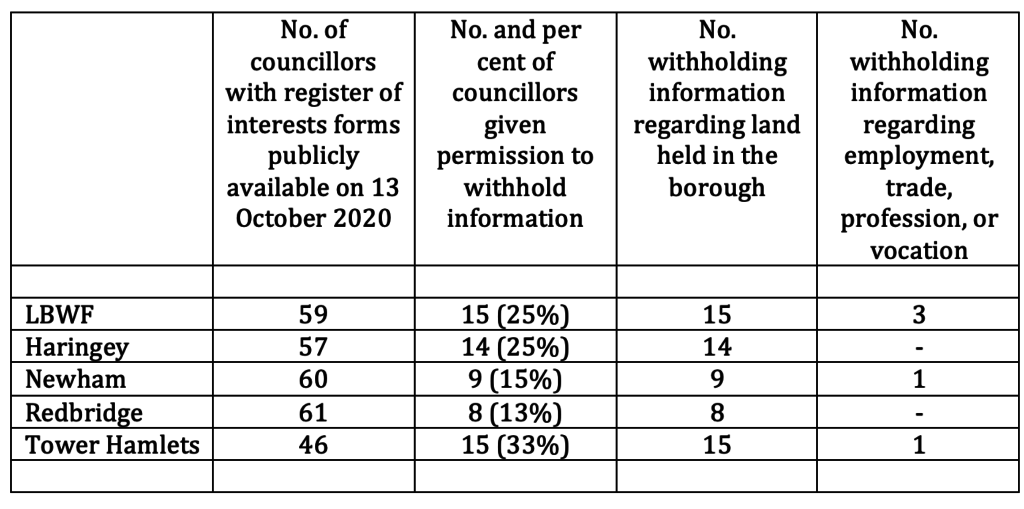

The table beneath looks at LBWF and its neighbours, and focuses in particular on councillors who are withholding information about, first, what land they hold in their home borough (which almost certainly will indicate where they live); and, second, their ‘employment, office, trade, profession or vocation’.

At first sight, the figures for LBWF seem unremarkable, midway between the extremes represented by Redbridge and Tower Hamlets. However, further research highlights that all is not necessarily as satisfactory as it seems.

For an internet investigation reveals that one of those local councillors who claims the protection of the legislation against ‘violence and intimidation’ has concurrently chosen to post the ‘sensitive’ information discussed with Mr. Hynes elsewhere in the public domain, using both a commercial website and LinkedIn, each of course then further amplified by Google and other search engines.

Acquainted with this evidence, Mr. Hynes comments as follows:

‘I was not aware when the original dispensation was granted that there was other publicly available information about…[XX] but even if I had I [sic] been made aware it would not have changed my view that the relevant details should not be published by the Council regardless of where else they may be published and available on the web.

In granting any dispensation my overriding concern is the safety and welfare of the councillor and…[their] family. If I reman satisfied that there remains a threat of violence or intimidation to the councillor if…[their]details were published by the Council then such details will not be published by the Council as in this case. Should a third party wish to track down…[XX’s ‘sensitive’ information] the most obvious route is to refer to the published Members Register of Interests, hence why we have chosen to withhold those details…I accept that there may be other ways that an individual can get those details…but that does not mean the council should also publish those details’.

For most ordinary residents, these observations will doubtless appear puzzling. Quite why Mr. Hynes is so adamant that, in cases such as this, he will only make decisions based upon his personal interaction with councillors, as opposed to a broader array of independent evidence, remains unexplained.

On the other hand, one thing that Mr. Hynes now does confirm is that, because of his stance, he has ended up in a position that many will perceive as rather uncomfortable, granting the councillor concerned permission to withhold allegedly ‘sensitive’ information from publication in the hyper-local Register, even while being aware that the same councillor is choosing to make the same information freely available across the entirety of the wider web.

To conclude, the protection which the legislation currently offers councillors is in itself reasonable and proportionate. However, the system also needs to be administered in a way that ensures it is not abused.

Has that happened here? The jury’s still out.