The London Fire Brigade and fire safety at LBWF’s Goddarts House, Walthamstow, sheltered housing: the anatomy of a shambles

This post examines the role played by the London Fire Brigade (LFB) in the ongoing scandal about fire safety at LBWF’s Goddarts House sheltered accommodation in Hoe Street, Walthamstow – 27 flats, with the ‘occupancy types’ officially described as ‘Elderly, Hearing Impairment, Mental Health, Sight Impairment, [and] Wheelchair Users’.

First, some general background about the legislation which governs fire safety at Goddarts, and what role the LFB plays in relation to it.

As regards the legislation, there are several statutes involved, but the most important, by far, is the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005 (hereafter FSO 2005).

For every building, it specifies, either the owner or someone ‘who has control of the premises’ is legally designated as ‘the responsible person’, and has two broad obligations, which are to

‘(a) take such general fire precautions as will ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the safety of any of his employees; and

(b) in relation to relevant persons who are not his employees, take such general fire precautions as may reasonably be required in the circumstances of the case to ensure that the premises are safe’.

Leading on from these introductory remarks, FSO 2005 then comprehensively fills in the detail of exactly what ‘the responsible person’ is accountable for, looking in turn at matters such as ‘Risk assessment’, ‘Fire-fighting and fire detection’, ‘Maintenance’, and ‘Training’.

So how has this piece of legislation worked out over recent years in terms of protecting those living at Goddarts?

As might be imagined, since Goddarts is council owned and run, senior Town Hall housing officers have succeeded each other as the designated ‘responsible person’, while it’s been the LFB’s duty to keep them up to the mark as regards FSO 2005, using measures such as site visits, fire safety audits (FSAs), and if necessary regulatory intervention, with the possibilities described, in ascending order of seriousness, as ‘broadly compliant (verbal advice)’; via ‘notification of minor deficiencies’, and ‘notification of deficiencies’; to ‘enforcement action/prosecution’, and ‘prohibition/prosecution action’.

That sets out the broad administrative arrangements, but the million-dollar question, of course, is whether or not the latter have been effective.

In the early months of 2020, two Waltham Forest residents separately questioned local and national LFB personnel about recent events at Goddarts, and on first sight, the responses they received appear broadly reassuring.

The LFB, it was asserted, had carried out seven FSAs between January 2015 and February 2019, and in the majority of instances, the result was a ‘broadly compliant (verbal advice)’ rating.

In August 2018, and then February 2019, it is true, the LFB had become more concerned, and issued two notifications of deficiencies (NODs), but part of the explanation for this, it was claimed, stemmed from a change in ‘National fire chiefs council’ guidance, rather than necessarily a deterioration of conditions on the ground.

Moreover, though the NODs to some extent upped the ante, they also seem to suggest that the LFB officers involved in the FSAs were very much on their toes. Thus, in one case, a NOD finding was based largely, perhaps solely, upon the eagle-eyed observation that, in contravention of the regulations, a wedge was being used to hold open Goddarts’ laundry room fire door.

However, if the LFB responses are scrutinised more closely, a decidedly less positive impression emerges.

First, it hardly inspires confidence to find that there is no agreement about either the total number of FSAs across the period, or their dates, with the August 2018 FSA, for example, in one account said to have occurred on Tuesday the 7th, in another the following Monday.

But, second, and of greater importance, it also appears that the FSAs were considerably less authoritative than might be expected.

In the interests of clarity, it is sensible to divide the period 2015-19 into two, and look first at the three and a half years or so bookended by the FSAs of January 2015 and August 2018.

This was a time, to repeat, when the LFB repeatedly rated observance of FSO 2005 at Goddarts as ‘broadly compliant (verbal advice)’.

Yet what’s very striking is that, as previous posts have discussed at some length, when LBWF’s agent, Ridge and Partners LLP, completed comprehensive Fire Risk Assessments (FRAs) for Goddarts in October 2015, March 2017, and June 2018, it came to what are, ostensibly at least, very different conclusions, on the first two occasions rating the ‘risk of fire’ at the property as ‘High’, the uppermost category possible, meaning that ‘Improvements should be undertaken urgently’, and on the third as ‘Moderate’ (‘Essential action must be made to reduce the risk’).

How can it be that these parallel sets of assessments, the FSAs and the FRAs, were so out of sync?

Did the LFB miss some salient evidence? Or was it that the LFB auditors worked diligently, but FSO 2005 required only a limited investigation, in other words the satisfaction of standards that were comparatively unexacting?

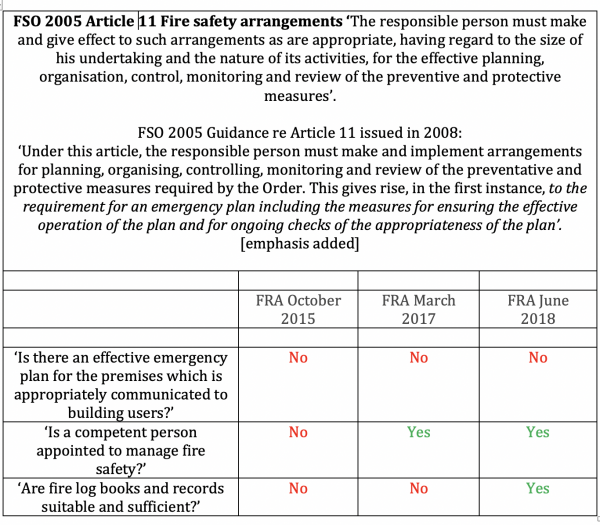

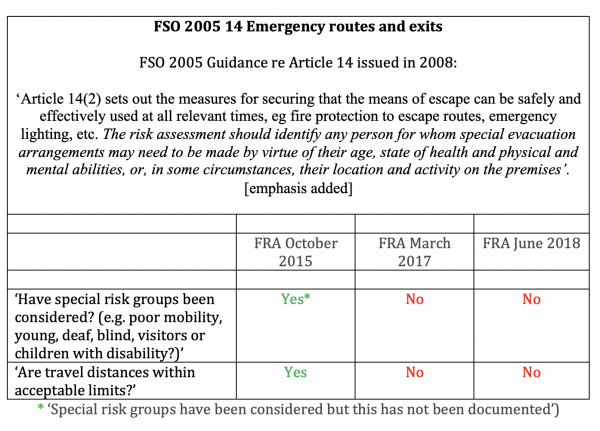

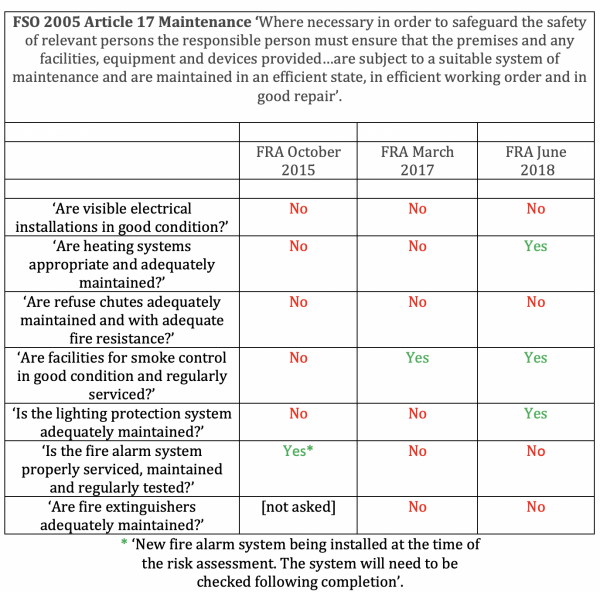

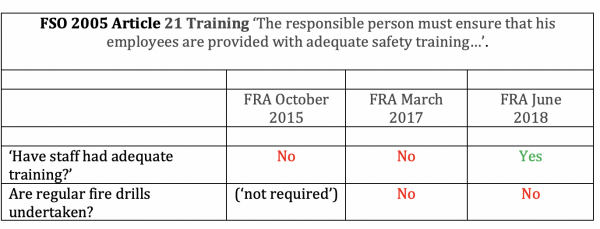

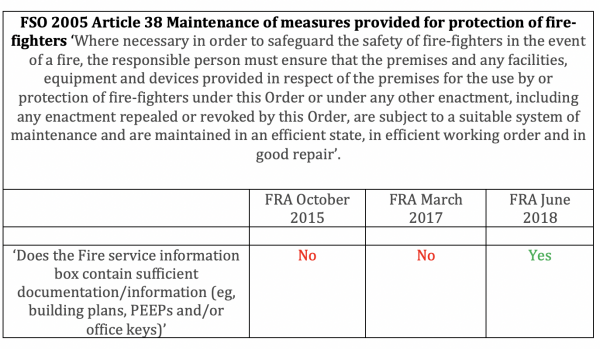

One way of answering these questions is to take some of FSO 2005’s central requirements, and use the detailed evidence that emerges from the three Ridge FRAs to assess whether they were being respected. Here are the results:

The inference, then, is clear. Measured against the legal standards of FSO 2005, there were always a significant number of safety measures during this period – ten in 2015, 13 in 2017, and eight in 2018 – that were non-compliant, leaving the residents at considerable risk.

Moreover, the direction of travel too was uncertain. For while seven fire safety measures were rated as improving over time, three others changed from compliant to non-compliant, while another three were rated as non-compliant throughout, the latter including the vital question of whether or not there was ‘an effective emergency plan for the premises’.

Quite why the LFB ever believed this unhappy situation to be ‘broadly compliant (verbal advice)’, and then stuck to its guns, is difficult to comprehend.

Questioned today, the LFB is unwilling to release the documents that might illuminate its assessors’ thinking, being of the view that ‘the correct balance of interest lies in making information about enforcement action available (published on our website) and specifically when people request it, but withholding the supporting information and evidence gathered during regulatory activities’.

However, it is certainly relevant to point out that the guidance on FSO 2005 which was issued in 2008 is forthright about when intervention beyond ‘broadly compliant (verbal advice)’ is mandatory:

‘An enforcement notice can only be served where the enforcing authority is of the opinion that the responsible person…has failed to comply with any provision of the Order (or of regulations made under it). The measures which could be required to be taken by a notice are limited to those which are necessary to ensure the failure is remedied’ [emphasis added].

A number of factors may explain why the LFB behaved as it did, but as this paragraph makes plain, lack of clarity in the legislation is not one of them.

Turning to the second part of the period, from August 2018 to February 2019, the LFB, as noted, suddenly became more proactive, and the two NODs of these years – dealing with deficient escape routes, insufficient consideration of those with impaired mobility, inadequate compartmentalisation, and so on – firmly registered its unease at the Goddarts failings.

Yet as before, some of the LFB’s conclusions were puzzling. One example will suffice.

In August 2018, the LFB NOD included the following observation addressed to the ‘responsible person’:

‘It was found that a “stay put” policy is in place. However, this has not been confirmed as suitable by a competent person as prescribed in your fire risk assessment’.

Five months later, the issue came up again, though this time with a surprising twist:

‘It was found that the fire risk assessment wrongly confirms that London Fire Brigade has agreed a “Stay Put” policy with Waltham Forest [council]’.

All this is bewildering in itself, but making things stranger still is the fact that the Ridge FRAs of October 2015, March 2017 and June 2018 all identify ‘stay put’ as the ‘evacuation policy’; while at the later two dates, it is also observed: ‘Waltham Forest Homes Operates [sic] a “stay put” policy for this scheme…it is understood this approach has been agreed with the London Fire Brigade’.

Choices about the suitability of ‘Stay Put’ as a policy are, of course, no light matter, and if not meticulously thought through may have extremely serious consequences. That there appears to have been such prolonged confusion about exactly what had been sanctioned at Goddarts, and in particular about whether the LFB was on board, seems deeply regrettable.

Taken as a whole, the LFB’s treatment of Goddarts from 2015 to 2019 looks shambolic. Few residents expected much from their landlord, LBWF. But they reasonably hoped that, as an independent organisation, the LFB would enforce the law without fear or favour.

In the light of events, they are entitled to feel more than a little aggrieved.

PS This post was updated on 28 May 2020 to correct a dating mistake in the tables.