LBWF and fire hazards in its housing stock: residents in Cann Hall’s John Walsh and Fred Wigg towers left in danger, as Labour averts its eyes

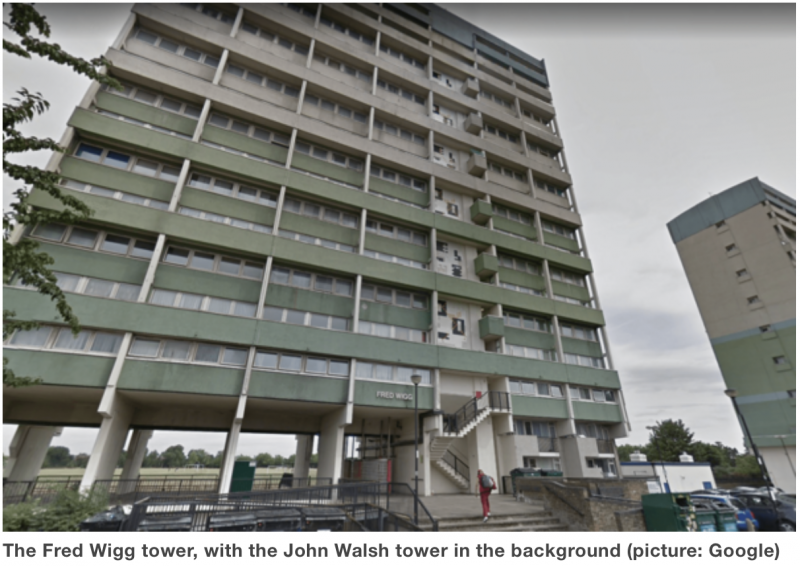

John Walsh and Fred Wigg tower blocks in Cann Hall are 15 storey identical twins, built in the 1960s, and each containing 117 flats.

It would be nice to state definitively how many people have lived there at any one time over the past decade, but nobody really seems to know, with (surprisingly) official estimates ranging from 230-ish to 700.

In 2011, Fred Wigg residents suffered a terrible fire, which saw two dozen people trapped as firefighters fought the flames. Subsequently the whole block was evacuated to temporary accomodation so that repairs could occur.

Given such a dismal history, and of course the June 2017 tragedy on the other side London at Grenfell Tower, it might be expected that, during the past few years, fire safety at Fred Wigg and John Walsh would be paramount, and absolutely top notch.

Astonishingly, however, the truth is very different.

Between April 2015 and June 2017, LBWF’s agent, Ridge, carried out three annual Fire Risk Assessments (FRAs) on each of the two tower blocks.

On every occasion, Ridge concluded that the ‘overall risk rating’ was ‘high’, the most serious possible, meaning that ‘Considerable resources might have to be allocated to reduce the the risk’ and ‘Improvements should be undertaken urgently‘ [emphasis added].

The message was hammered home in the more detailed findings. Each year, Ridge examined the same 65 or so metrics (covering ‘Control of Sources of Ignition’, ‘Control of Sources of Fuel’, ‘Compartmentalisation’, ‘Fire Procedures and Training’, ‘Means of Escape’, and so on’), and discovered that an extraordinary number were consistently found wanting, with the average across the three years for the two blocks no less than a startling 28, or 43 per cent per annum.

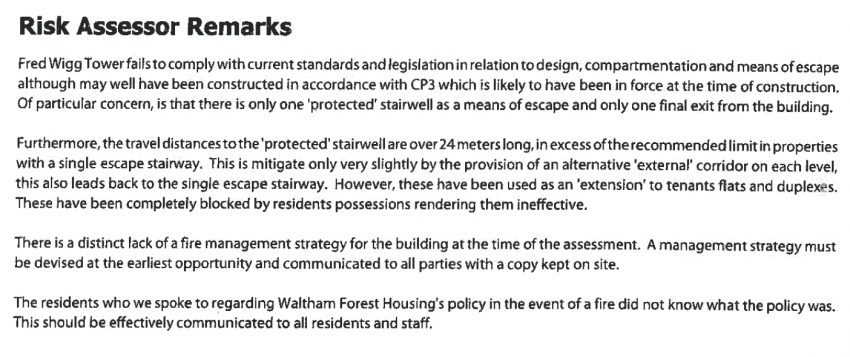

Indeed, so alarming did Ridge believe the situation to be that it added virtually the same stringent warning to each of the six reports, with that for Fred Wigg in 2016-17 being typical:

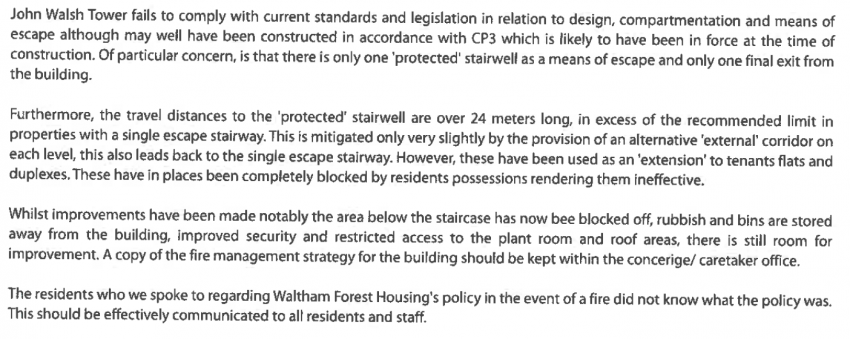

In July 2018, Ridge returned to Fred Wigg and John Walsh, and found that there had been a degree of improvement. Yet in each block, 20 of the 68 metrics scrutinised – that is nearly a third – still failed to pass muster, and in both cases the overall rating (using new terminology) was ‘substantial’, as before the most serious possible. The risk assessor’s remarks largely remained unchanged:

So, as the evidence summarised shows, for just over three years between April 2015 and July 2018, the residents of John Walsh and Fred Wigg were left to live in dangerous circumstances, despite Ridge’s repeated warnings. True, the blocks had been completed in a different era, with less stringent safety standards, but this is no mitigation. All FRAs took the unhelpful design into account, and recommended the appropriate measures to ensure safety. Most of the latter were relatively inexpensive. The fact that throughout this period such a simple but crucial step as effectively ensuring residents and staff knew what to do in the event of a fire was again and again overlooked graphically demonstrates the magnitude and character of the failure.

How did this situation come about? More specifically, how was it that a Labour council – that is, a council run by a party which had been set up to defend the poor – could behave in such a reprehensible fashion?

Part of the explanation lies with the wider context.

For from 2013 to 2018 LBWF was pursuing a £40m. plan to completely redevelop John Walsh and Fred Wigg in conjunction with commercial partners, and in the process turn some of the social provision into private apartments; and while, in the end, this came to nothing, it did inevitably impact on the way that the blocks’ residents were treated.

LBWF, in short, wanted to rehouse as many residents as possible, as quickly as possible, so as not to delay the start of the rebuilding process.

But to those on the receiving end, all this seemed very threatening. The arithmetic didn’t stack up. There were fewer flats planned for them in the new scheme, so what about those who there wouldn’t be room for? Of even more pressing concern, where were they all going to be housed while the building work proceeded?

As it was obliged to do, LBWF tried to allay these concerns through consultation, but the mechanisms were flawed, and information sharing was poor. Discontent mushroomed. There were complaints about intimidation, and the deliberate fostering of division. The chair of the Fred Wigg and John Walsh Tenants and Residents Association fumed at ‘the increasing number of mistakes and gaps in the council’s housing service’. Worries about a fire lurked just below the surface. A plan to remove glass balcony divide doors in order to provide a secondary escape route was greeted with anger, not least because it compromised residents’ privacy, appeared out of the blue, and ignored much better alternatives. The atmosphere rapidly became very sour indeed.

Against this background, it is not difficult to see why fire safety as a whole slipped down the Town Hall agenda. The focus was on gaining possession of the blocks. The goal of achieving a high profile and very profitable redevelopment opportunity beckoned. And if some complained, they could be – and were – dismissed as trouble-makers. The financial logic set the parameters.

A second relevant factor is the stance taken by Cann Hall’s three Labour councillors – Patrick Edwards, Sally Littlejohn, and Keith Rayner.

It needs to be underlined, to start with, that all Waltham Forest councillors always have been well positioned to evaluate fire safety in particular locations, because not only can they obtain specific FRAs without having to use LBWF’s tortuous Freedom of Information Act procedures, they also have access to a range of tailored resources such as the London Fire Brigade’s Councillor Guide on fire safety for use during council meetings (which cautions ‘Do not make assumptions that fire safety is being actively or effectively managed in purpose-built blocks of flats and maisonettes in your borough. Councillors can make their boroughs safer by scrutinising how responsibilities for fire safety are met and ensuring that fire safety in your borough is continuously being monitored and improved’).

So what did the Cann Hall trio do with regard to the issues at John Walsh and Fred Wigg?

Clearly, all three recognised the tenants’ discontent, but they also had good reason to know that their senior colleagues wanted redevelopment, were unsympathetic to those who failed to uphold the party line, and had previously instituted internal disciplinary proceedings against the outspoken. The outcome was predictable. On one occasion, as an earlier post noted, Cllr. Edwards broke ranks, and criticised aspects of the ongoing strategy (‘”I support redeveloping Fred Wigg and John Walsh but it’s important that the people who are going to live there back it too. We’ve moved a long way from the era where people were told what was good for them to one where they can actively voice their future.That voice should come through a properly conducted independent residents ballot”’). But for the most part, in public at least, there was only a deafening silence.

What throws this into particularly sharp relief is the fact that on other matters the same councillors could be both vocal and energetic. Thus, for example, when, during these years, LBWF increasingly began to focus borough-wide on (in its jargon) the ‘rising prosperity’ demographic as the key to successful redevelopment, in Cann Hall the trio reacted very positively. A closed pub, they promised, would be sold to the fashionable operator Antic, and given an up-market makeover. A plan for the area would be created, and feature a ‘pop-up’ cinema in an old public toilet and a new glass-roofed cafe in one of the local churches. The area would receive considerable public infrastructure investment, £500,00 in one iteration, £750,000 in another. Public art, including a bespoke, tiled mural on a local shop wall costing £40,000, would flourish. And so on.

Of course, as this blog has documented, few if any of these promises were realised, but for the purposes of the argument advanced here that matters little: the important point is about the choice of priorities.

However, it may be objected, perhaps the councillors were raising fire safety issues, but, quietly and in private, believing that given the circumstances this was the best way to make progress?

Perhaps they were.

But what can be said without fear of contradiction is that, since the FRAs largely repeated the same warnings on four separate occasions, if such petitioning was occurring, it seems to have been remarkably ineffective, suggesting that the councillors were either ill-informed about specifics, or unwilling to really commit, maybe over concerned about protecting their political careers.

In short, therefore, this was not the Cann Hall trio’s finest hour.

Postscript

LBWF is keen to inform this blog that many of the safety issues at the towers are now resolved, following energetic action over the past year.

This may or may not be true, and independent verification is awaited.

But if the towers are presently safe, that can only be a good thing.

Nevertheless, the possible turnaround does not of course erase what happened in the very recent past, and the blunt fact that, despite many warnings, and the urgency of the need for change, LBWF left a large number of residents to languish in blatantly unsafe conditions – certainly a stain on its reputation.