How the Labour Party funds local elections in Waltham Forest: further embarrassing revelations

Two previous posts have looked at how Labour in Waltham Forest manages its finances, and suggested that all is not as it should be, particularly with respect to transparency.

What follows examines some new data that appreciably amplifies this earlier conclusion.

After local elections, political parties are required to account for their expenditure to the Electoral Commission (EC) by submitting returns for all candidates listing how they financed their campaigns and what exactly they spent their money on.

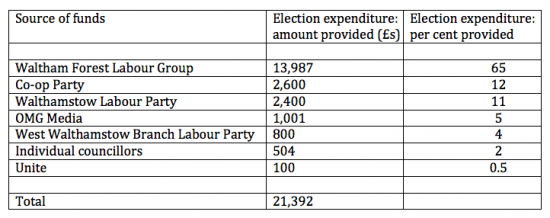

Focusing on Labour at the 2018 contest, these returns reveal, in aggregate terms, the following about funding:

As can be seen, Labour spent £21,392 in all, and two-thirds of the total was provided by something called the Waltham Forest Labour Group (WFLG). So what is this somewhat mysteriously titled entity?

The WFLG is apparently made up of sitting councillors and nobody else. That is interesting in itself. But the most significant thing about the WFLG is that according to the Electoral Commission it is not a registered political party, rather what is termed an unincorporated association. And the reason why this is significant is that the EC treats registered political parties and unincorporated associations differently.

A senior EC officer explains all:

‘I confirm that the Waltham Forest Labour Group is not a registered political party.

Under the Political Parties Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (PPERA), unincorporated associations must register with us when they make political contributions of more than £25,000 in a calendar year. Political contributions include donations and loans made to political parties, organisations that campaign in elections, and individuals in elective office like MPs or members of devolved legislatures (MLAs, AMs or MSPs).

As well as registering with us, unincorporated associations must tell us about the reportable gifts they receive. This information is published on the register of unincorporated associations and the register of recordable gifts to unincorporated associations.

Reportable gifts include…a single gift of more than £7,500;…two or more gifts given by the same person in the same calendar year which total more than £7,500; and…any additional gifts given by source that they have already reported as having given a gift in that calendar year, if the gifts have a value of, or add up to, more than £1,500.

Under PPERA, political parties registered in Great Britain and Northern Ireland must report cash and non-cash donations and borrowing to the Commission on a quarterly basis. Political parties must report all donations and borrowing over £7,500 relating to the central party, or over £1,500 relating to an accounting unit [AU]. This includes aggregates of donations and loans from the same source during the calendar year.

In addition, all parties and certain accounting units must submit an annual statement of accounts to us, which sets out the party’s / AU’s annual income and expense’.

What this boils down to, therefore, is that as an unincorporated association, the WFLG has to reveal significantly less about itself to the EC (and thus the public) than do organisations classified as registered political parties, for example the three local constituency Labour parties (CLPs).

So what else can be ascertained about the WFLG? One obvious question to ask is where the WFLG gets its money from. Many will no doubt assume that the answer is the CLPs, because of course they do a good deal of fundraising, and are the visible face of Labour on the ground.

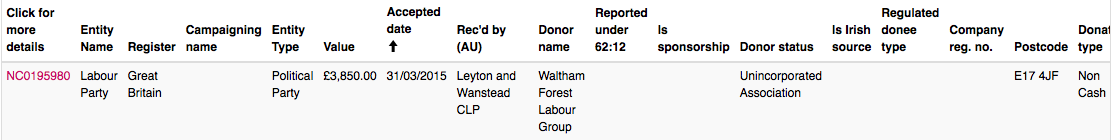

Yet searching though the EC registers reveals that in the years since 2015, there has been only one recorded transaction between the WFLG and the CLPs, and on this occasion, perhaps surprisingly, the former was the benefactor rather than the beneficiary:

In fact, what appears to happen is that the WFLG raises at least some of its income internally, i.e. from the sitting councillors, charging them annually a percentage of their allowances. However, as to whether the WFLG also receives gifts from third parties, the situation is unclear. There is nothing on the EC registers, but as has already been noted, since sums below £7,500 p.a. do not have to be reported, it is possible that one or more smaller amounts of money may still have been received.

The final point to make about the WFLG is that it is remarkably reclusive. There is not a single reference to the organisation on Google. Challenged to fill in the gaps, backbenchers shrug their shoulders, and claim they are kept in the dark. Does the WFLG have a constitution? Does it compile annual accounts? Does it take decisions in a structured and democratic way? At present, there is no way of telling.

For anyone who believes in democracy, all this is without doubt embarrassing. In effect, voters are being shortchanged, because they are unable to be wholly sure about where Labour is getting its money from, and thus cannot be certain that everything is above board and legal. And apprehensions here are magnified because in other parts of the country unincorporated associations appear to have been used as a way of circumventing EC funding rules, as these recent cases demonstrate:

https://www.thenational.scot/news/16885624.secretive-tory-club-who-funnelled-100000-to-party-coffers-fined-by-electoral-commission/

https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2015/mar/13/conservative-party-given-nearly-500k-in-concealed-donations

It must be stressed that there is no evidence that anything of this kind has occurred in Waltham Forest. But it is also true that Labour’s reputation is hardly enhanced by its choice of a methodology that is so patently lacking in transparency.

So why has the party ended up in such an unwholesome position? For the current Labour Group leadership, control of election finance brings some clear potential advantages, particularly in terms of reinforcing loyalty and patronage. Put bluntly, most backbenchers will think twice before deviating from the agreed line if they know that dissent may mean lower levels of support at the next election. Similarly, and further down the food chain, the leadership knows that by controlling the purse strings, it can limit the progress of the left in the CLPs, always an attractive objective given the party’s continuing and often vicious internecine warfare.

Of course some amongst the Labour grassroots denounce what they see as a form of chicanery, and recently have pushed through CLP motions deploring its continuation. Nevertheless, it is very noticeable that this issue has never become a major cause, and in fact, despite the alleged Corby-inspired influx of young and educated professionals, internal finance remains a Cinderella subject, with one senior Labour office-holder graphically describing to this blog the look of boredom on members’ faces whenever the subject is raised.

In conclusion, this is another case of almost pure Waltham Forest-itis. What’s wrong is evident, as is the solution. But there is not enough conviction about to make the change happen.

And meanwhile the only losers are, once again, the local residents.