LBWF and public-private partnerships: (2) North London Ltd.

LBWF’s relationship with North London Ltd. (NLL) illuminates a second way of organising public-private partnerships.

NLL is a private company, formed in 2005, whose business is ‘Other service activities not elsewhere classified’.

LBWF has close links with NLL, not (as with NPS London Ltd.) because of share ownership, but rather because of, first, mutual involvement in a network of allied institutions, and second, the fact that for the bulk of its history NLL has been something of a factotum, the authority’s chosen vehicle for the local implementation of a variety of programmes, some originating in Waltham Forest, others elsewhere.

Thus, in the years to 2012, when LBWF paid NLL in all £455,279, it made 62 separate transfers to the company relating to a dozen or so different activities.

So how has this arrangement worked out in practice? Has it proved an efficacious way of achieving LBWF’s chosen ends?

Looking first at outputs and outcomes, the answer must be a resounding ‘no’. Linked posts have already told much of the story. LBWF has been unable to account adequately for a large portion of the monies it supplied. Formal audits show that individual NLL programmes such as Exporting Success and City Growth markedly underachieved. The fiasco that was Leyton Olympic Market speaks for itself.

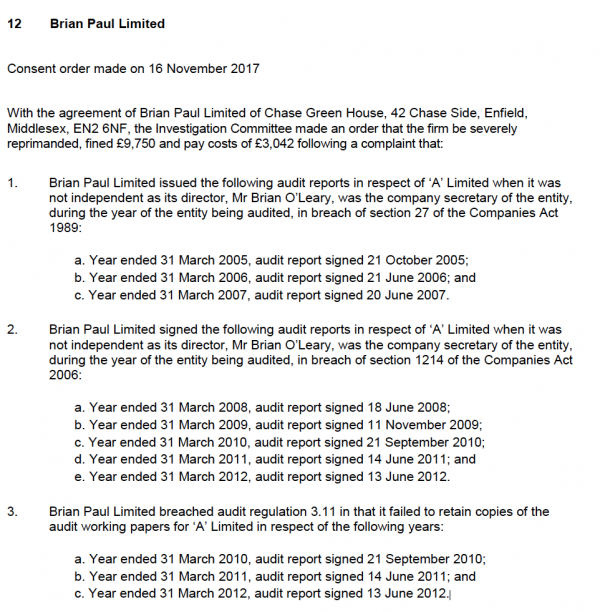

Delving behind the scenes, and in particular focusing on NLL’s governance, is also disquieting. In late 2017, the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW) castigated a company called Brian Paul Ltd., which over time had audited an entity described as ‘“A” Limited’, in a very clear and forthright judgement:

The significance of this is that ‘”A” Limited’ turns out to be…NLL.

So, to be absolutely clear, it is now established that LBWF was paying public money to a company whose auditor, as the ICAEW now judges, stood in breach of the law.

This is surprising stuff in itself. But what makes it doubly so is the fact that no one at the time seems to have spotted what was going on.

LBWF had, and has, an obligation to complete due diligence on those organisations that it finances. It is universally understood that an auditor has to be independent, and most definitely not part of the company being audited. Moreover, the core facts cited by the ICAEW have never been hidden, and in fact were often plainly stated in publicly available documents lodged at Companies House. The truth is that LBWF missed – or ignored – what was staring it in the face.

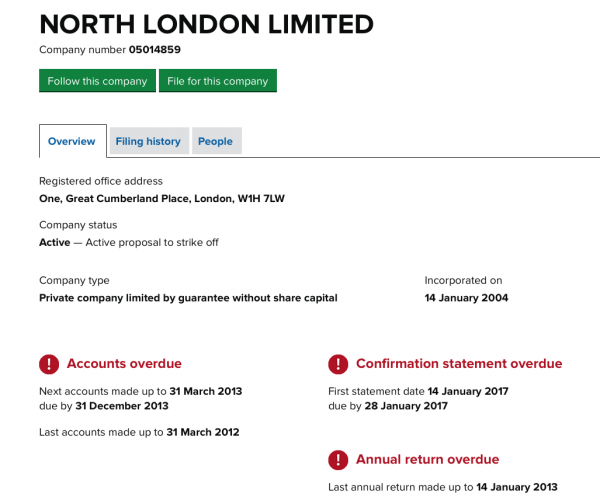

Finally on governance, it is worth adding that since 2012, NLL’s trajectory has taken a series of unusual and perplexing turns. In August 2013, The Gazette published a winding up notice for the company, with a meeting of creditors also scheduled, but no further action (for example, a liquidator’s report) followed. Four years later, with NLL still listed as ‘active’, Companies House recorded first that compulsory strike off was threatened, and then that this had been suspended because of one or more objections. Today, NLL appears to be in limbo:

Needless to say, such a situation hardly inspires confidence in any of the parties involved.

Needless to say, such a situation hardly inspires confidence in any of the parties involved.

So what lessons can be learnt from the NPS London Ltd. and NLL case studies? Public-private partnerships in local government affairs are clearly here to stay. But their success depends upon those with responsibility for public money delivering appropriate due diligence, continuous monitoring of expenditure and outputs, and a proper final reckoning.

LBWF’s track record in such matters is at best mixed, and so whether the required oversight will be forthcoming remains questionable.

Perhaps its time for some sustained debate locally about the way forward. Given their ascendency, it will be interesting in particular to discover what the Momentum crew believe is the solution. Indeed, this may turn out to be something of a litmus test for them, an issue which allows the rest of us to judge whether they are serious about political change, or (as it appears today) just wedded to sloganeering.